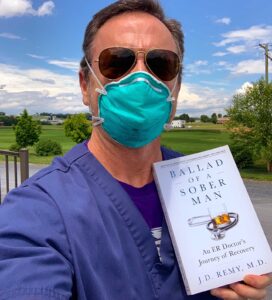

Ballad of a Sober Man details alum's experience as a patient in a treatment facility and his return to medicine in the midst of a pandemic

J.D. Remy, a pen name used to protect family and personal identity, graduated from Lafayette College in 1988 with an interdisciplinary degree in psychology and biology and went on to medical school at George Washington University, finishing in 1992. He did his residency in emergency medicine at University of Maryland in Baltimore.

By Bryan Hay

As his career as an emergency physician advanced, so did J.D. Remy’s overblown sense of privilege and entitlement.

With the growing ego came the alcohol. It was there to impress guests at parties. In quieter times and places, it was within easy reach as a balm to ease the ongoing pressures associated with practicing medicine in a busy emergency department.

In his new book, Ballad of a Sober Man: An ER Doctor’s Journey of Recovery, Remy, a fictional pen name used by a Lafayette College alumnus, chronicles his journey from active alcoholic to his humbling experience as a patient in a residential treatment facility, and ultimately his return to medicine just as the coronavirus pandemic was unfolding. Published by AnnElise Publications, it’s set for release Oct. 6 on Amazon and other online booksellers.

His story, which reads more like a novel than an autobiography, unleashes early graphic descriptions of violations of his senses—the bitterness of Librium dissolving in the mouth or overpowering aromas from fellow inpatients as he progressed through his early days in recovery.

His days at Lafayette College receive a mention in chapter two, which details his experiences in a residential treatment center:

This is gut wrenching, I can’t do this. I’m not eighteen years old anymore and I am not in Ruef Hall at Lafayette College skimming through some English 101 assignment while getting ready to head over with Warren and Andy to Theta Chi for pub night. I’m a grown-ass man with three children and a hugely important job and my brain is buzzing and stuttering like a faulty streetlamp and I can’t comprehend the sentence I’m reading, nor remember the one I just finished. My brain is dead, and this is all very hopeless and futile. I’m scared. My most important asset—my brain—is offline. I’m an invalid.

Following are excerpts from a recent conversation with Remy about the book and his journey.

The opening chapter deals with your entry into a detox facility at age 50. Please describe that point in your life and the spark that inspired your book.

My drinking career hit its nadir just prior to my 50th birthday. I had accumulated a horrific track record of drinking over years, the consequences of which eventually came crashing down on me on Nov. 3, 2016. So I entered into rehab with an entire adult life of alcoholism behind me. I like to think of 50 as the halfway mark at this point in life. And so I’m looking forward to another 50 years, alcohol free.

Once out of rehab, part of my recovery and therapy—and remaining in alcoholic remission —required and necessitated that I set pen to paper. I started by journaling my thoughts informally in a spiral notebook. Every morning, I wrote some thoughts down, including some passages about memories from my rehab. And I wrote about my children and my longing to return to work. I did it daily without fail, religiously. After several months, I realized I had quite a number of pages. I went back and I reread some of my early writing and realized, hey, this might make a pretty decent memoir.

Did you have a specific audience in mind?

I knew that I could include some flashbacks of my active drinking years. But mainly I wanted to keep the majority of the text about recovery and write the book in the solution instead of in the problem. And so, as it came together, I realized perhaps what I’m doing is creating something that others who are bound by active drinking and active addiction can read and say, hey, this guy managed to break free of the gravitational pull of alcoholism and addiction and reclaim large swathes of his life, so perhaps I can as well.

I’m hoping to reach out to the alcoholics who still suffer and, more specifically, the professional alcoholics and addicts who quietly suffer and long for help, but are terrified of coming out for fear of wrecked reputations and putting their professional licenses in jeopardy. This is not an easy time to be a medical professional.

When you think of a medical doctor, maybe your family physician, it’s sometimes hard to think of him or her as being flawed or in any way frail or fallible. How does pressure from that image increase the chances of addiction?

There’s an enormous amount of pressure on medical providers to be perfect people day in and day out when we really are as vulnerable as anybody else, sometimes even more so because we are expected to hide our character defects.

So as a result, we flail, looking for an outlet. And that outlet often ends up being some really bad behavior, whether it be alcohol or drug diversions, gambling or sexual immorality. We find ourselves, to a certain degree, having these tiny little secret lives, where our alter egos allow our imperfections to come out full force, enabling us to experience a temporary reprieve from the outside world. We have our little secret bubbles where we can relax as normal, flawed human beings. For me, that was alcohol.

Is there anything from your time at Lafayette that aided your journey?

I’m glad you brought up Lafayette. First, I want to say, first and foremost, that when I went to Lafayette in the 1980s drinking and an alcohol-based social life was the mainstay on campus. But in no way do I attribute my Lafayette experience as contributing to my disease. I think it was just the opposite. I was an alcoholic, and used the party scene on campus to feed my addiction. Everyone else did it, and I felt routinely validated in my behaviors. For me, it was affirmation that I was ‘just like the crowd.’

Overall, Lafayette did a great job of preparing me to be a physician and instilled a certain code of ethics in me. As I took my classes and experienced the rigors of a Lafayette course load, I saw the way adults are supposed to behave.

It set the tone for me to become the kind of professional I am, but decades later it also worked to my benefit, setting the tone for me to work rigorously, on a daily basis, to maintain my recovery and my sobriety.

In the book, you talk about reentering emergency medicine just as the pandemic was spreading. You didn’t have a chance to celebrate your sobriety. What was that like?

Before returning to medicine, I was placed in a professional monitoring program after treatment, and I got a job stocking shelves in a supermarket to teach me humility and how to mitigate narcissism.

Let me tell you, there’s nothing like being the president of your own medical staff and then a couple years later stocking shelves at a supermarket. From there I graduated to teaching on a local college campus in the field of emergency medicine. And from there I moved to an urgent clinic where I saw patients with very minor ailments. As I advanced and my overseers in the monitoring program saw that I was doing well, I was allowed to return to emergency medicine.

And, of course, I returned to emergency medicine just as I’m getting my groove back, and then we are all hit with the worst pandemic in a century.

How did your experience prepare you to deal with COVID-19?

I think of the Serenity Prayer and accept the things I cannot change and find the courage to change the things I can.

We see people on a daily basis and in the media decompensating, completely losing it during the shutdowns and the isolation. And while being isolated is not healthy for a newly recovering alcoholic or addict, it allows those of us who have been at this recovery thing for a while to seek out those who are struggling, and try to assist them in their problem.

People may not realize there exists a small army of professionals in long-term recovery who are not only able to swim in the COVID environment but are able to pull others who are struggling badly onto the proverbial life raft with them.

So again, the recovery has allowed me to successfully negotiate the COVID pandemic one day at a time and try to change what’s within my control.

Do you find that you’re a more sensitive, empathetic physician now?

Much more so. I once had a condescending kind of approach to the addicted. And I think a lot of that was embedded in personal self-loathing because I probably knew, deep down, that I was one of them, one of those skid row alcoholics, I just happened to be showered and donning a white coat.

I practice at a hospital that borders a big university campus here in the Shenandoah Valley. And I used to look at the students who came in heavily intoxicated with alcohol poisoning or trauma related to alcoholism, and probably deep down saw myself there. I saw them, and I treated them with some disdain, probably, which was a direct result of my habits.

Now that I’m out of the closet with my drinking history and in long-term recovery, I feel like I’m more of an empath. I not only treat their condition at the bedside, but when we are wrapping things up and they are about to be discharged or, if they’re bad enough to be admitted, I sit with them. Sometimes I even divulge my story; I feel it lends credence to what I tell them. And if they benefit even slightly, I’ve done my job. It is a win-win.