By Stephen Wilson

Owen McLeod doesn’t think of himself as a writer.

Writers feel that compulsive pull to put pen to paper every day and a misery that yokes their shoulders if it doesn’t happen … or, conversely and ironically, the misery when it does.

Writers have piles of yellow legal pads cluttering up an office. Writers slog through reams and reams of phrases, metaphors, and poetic angst. And then slog some more through new ideas, crappy drafts, and pieces they thought were final.

Of course, McLeod does the same, but his writer compulsion ebbs and flows. He’s half-time obsessed. Months on. Months off.

So he can’t be a writer.

McLeod instead is a philosopher, an analytical philosopher to be exact who specializes in distributive justice. He is an associate professor with three years of teaching at Yale. He deals in assumptions—both identifying them and then questioning them. He’s a builder of ideas. He’s a refuter of ideas.

McLeod instead is a philosopher, an analytical philosopher to be exact who specializes in distributive justice. He is an associate professor with three years of teaching at Yale. He deals in assumptions—both identifying them and then questioning them. He’s a builder of ideas. He’s a refuter of ideas.

When he needs a break from that portion of his mind, he turns to pottery, something physical and tangible that isn’t yardwork, the typical outlet for urban thinkers who seek a modicum of physical effort.

Throwing clay began eight years ago as a happy accident. The mailbox held a flyer for continuing education classes. McLeod saw ceramics and on a whim signed up. He says he’s terrible at it but loves it. One course led to another, and soon his home was rife with teacups and vases.

Still, niggling at him was the idea of writing. Sure, he had penned papers for academic journals. Yes, he did write some poems as an undergrad the way all undergrads do as they pine, grieve their pining, and pine again. But he never took a literature or creative writing course. His occasional poetic urge fell away under the heft of graduate school demands.

Then in the summer of 2014, McLeod was reading the Paris Review, a collection of their old interviews with novelists. When he finished the fiction writer interviews, maybe, he thought, he should read what the poets have to say.

He hadn’t read a poem in 25 years.

Snap.

Like that, he is obsessed. He is reading. He is … wait for it … writing. He soon reaches out to Lee Upton, then Francis A. March Professor of English and writer-in-residence, to confess, as poets do, his obsession. She encourages him to audit her history of poetry class. He does.

From Dickinson to Ashbery, he is reading through the ages. He’d read, then write, then imitate, then edit, then struggle, then quit, and then start again.

Then he had to admit it: He was a poet. And a potter and a philosopher. Maybe not in that order.

From 2014, when he started that class, through 2015 when he had a poem published, to 2017 when his manuscript was accepted for publication, McLeod wrote in sporadic fury.

During the lag between acceptance and its 2019 release, his writing slowed.

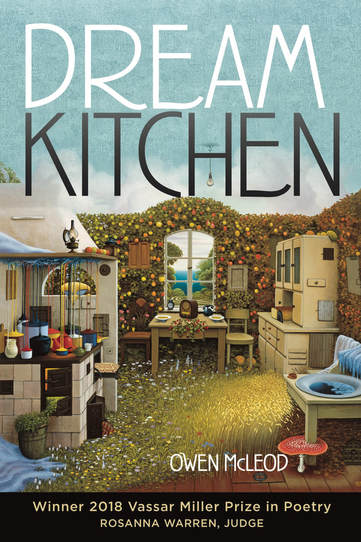

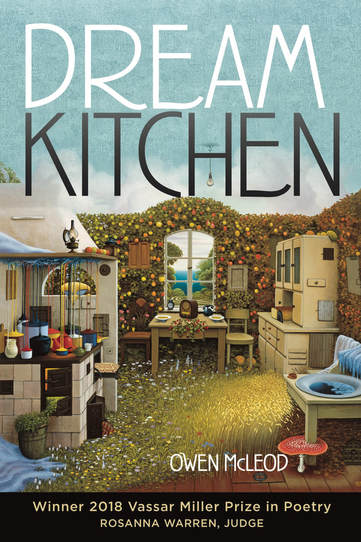

The book, Dream Kitchen, is no wolf in sheep’s clothing. It earned the 2018 Vassar Miller Prize in Poetry. He had poems placed in Ploughshares and The Southern Review.

He then supported it with readings, and then, bam, he was invigorated again.

He then supported it with readings, and then, bam, he was invigorated again.

He kept writing actively through his 2019 sabbatical year until he was sitting on another manuscript.

By early 2020, manuscript in hand, he was poetically exhausted.

The poetry mood ebbed. The philosophy mood flowed. His throwing wheel still turned.

He read from his new poems at the recent Jean Corrie Poetry Reading.

“If you want to be bummed out, then you have come to the right place,” he says. His writing personality is dark, seeking to comprehend what is unsettling and disturbing about life.

“Poets suffer,” he says.

He served as judge at the annual event, selecting from a wide range of submissions the top two poems from first-, second-, and third-year students.

At the virtual gathering, Maya Nylund ’23 and Fatima Cham ’23 read their first and second prize poems, respectively. Both poems wrestle profoundly, politically, and personally with issues of death by suicide and racial profiling by police.

Poets do suffer as they try to understand suffering. They also inspire action however tenuous and fragile.

Following the students, McLeod then read poems about the vengeful placement of a cinder block hidden among roadside leaves, Jesus texting him a random string of emojis, mental illness, an amputee, teeth, and an action figure that affirms your life when you find the hidden button.

“People naturally assume that poetry is confessional, especially if there is an ‘I’ in it,” he says. “While there are some that are autobiographical, some are pure fiction, and many are blend. Either way I want them to be accessible and pack some emotional punch.”

At the reading he smacks the listeners around a bit … to their delight.

But his new manuscript? Well, that needs time to sit. Only with critical distance and the right poetic mood can he take up the mantle of writer again.

“It’s not as if anyone is waiting for my next book to come out,” he says.

Seems like a refutable claim.

McLeod instead is a philosopher, an analytical philosopher to be exact who specializes in distributive justice. He is an associate professor with three years of teaching at Yale. He deals in assumptions—both identifying them and then questioning them. He’s a builder of ideas. He’s a refuter of ideas.

McLeod instead is a philosopher, an analytical philosopher to be exact who specializes in distributive justice. He is an associate professor with three years of teaching at Yale. He deals in assumptions—both identifying them and then questioning them. He’s a builder of ideas. He’s a refuter of ideas. He then supported it with readings, and then, bam, he was invigorated again.

He then supported it with readings, and then, bam, he was invigorated again.