A chat with former Lafayette provost June Schlueter about her latest book, which sheds new light on the source of the famous playwright’s work

By Stella Katsipoutis-Varkanis

Charles A. Dana Professor Emerita of English and former Lafayette provost June Schlueter has teamed up with independent scholar Dennis McCarthy to send shockwaves through the Shakespeare community for a second time.

Charles A. Dana Professor Emerita of English and former Lafayette provost June Schlueter has teamed up with independent scholar Dennis McCarthy to send shockwaves through the Shakespeare community for a second time.

In 2018, the literary duo discovered a manuscript written in 1576 by George North and claimed it was the Bard of Avon’s inspiration behind 11 of his plays. The story made national and international headlines. In fact, it even earned a front-page spot in The New York Times.

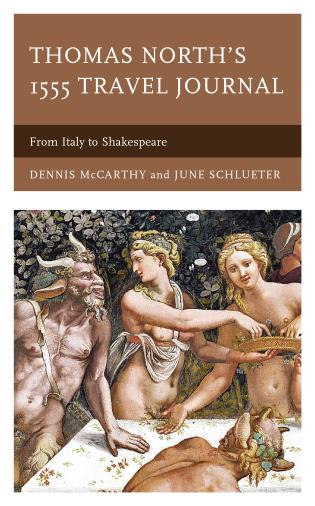

Now, with the release of their new book earlier this year—Thomas North’s 1555 Travel Journal: From Italy to Shakespeare—Schlueter and McCarthy are shaking things up again by delving even deeper into the question: What if someone else wrote Shakespeare’s plays first?

We sat down to chat with Schlueter about the publication, which suggests that England’s most famous playwright borrowed from Thomas North (likely George’s cousin) to create two of his late works: Henry VIII and A Winter’s Tale.

How did your partnership with Dennis McCarthy come about?

In 2011, I published a piece in Shakespeare Quarterly on the Peacham drawing, the only surviving contemporary sketch of a scene from a Shakespeare play. Dennis read the article and was very interested, so he emailed me about it. After several months of conversations about the drawing, he brought up the matter of Thomas North and the research he was doing on him. We exchanged many more emails before I was persuaded that he was on to something, which is when I joined him.

What is the possible connection between Shakespeare and Thomas North that you and Dennis aim to shed light on in your newest book?

The book is about a little-known travel journal from 1555 that was kept by Thomas North. North was on a delegation from England to the pope in Italy under Queen Mary I. The queen was Catholic, and she was trying to reconcile England and the pope. For six months, North kept careful notes about his journey to Italy and back. That journal had been published in part in the 18th century. Dennis and I dug it out, intending to publish it in its entirety, when we found that there were some interesting phrases, passages, stories, and characters in it that made us both think of Shakespeare.

After searching through various online databases, we discovered that many phrases and passages were unique to North and Shakespeare. So, it turned into a source study. We were interested in seeing the sources that Shakespeare used, and we found that—even though Shakespeareans have known for a long time that Shakespeare borrowed from North’s translation of Plutarch’s Lives—those sources went way beyond Plutarch’s Lives to all of North’s other writings, including his travel journal.

But why, we asked, would he have turned to North’s translation of, say, The Dial of Princes or The Moral Philosophy of Doni for material for The Winter’s Tale—or for any of the romances or comedies? What could he possibly have hoped to find there? The more matches Dennis found, the more it became clear to us that North must have written plays that also contained such language and that were Shakespeare’s immediate source. Shakespeare, then, was not borrowing from North’s translations; decades after their original composition, he was adapting North’s plays.

We’ve all heard of Shakespeare, but North isn’t exactly a household name. Who was he?

North, who was 29 years older than Shakespeare, was born in 1535 as the unfortunate second son of Edward North. I say ‘unfortunate’ because the tradition then was that the firstborn son inherited everything, and the second son next to nothing. He had to make his own way in the world, and the path he chose was literary. North was well educated—probably at Cambridge, though we don’t have the record on his education. He was friends with lots of higher-ups, including Queen Elizabeth I, [Robert Dudley] the First Earl of Leicester, and others. At age 20, he was the page to the Bishop of Ely, which is how he got to go on that delegation to Rome. He also worked as a translator, and he was highly praised for his translation of Plutarch’s Lives. He did three other major translations as well. We’re not sure how North spent his final years, but we know he was still translating in 1602. He had a long career, distinguished in terms of the response of the literate, but late in life money was a problem.

How did you come across North’s journal?

My husband, Paul Schlueter, who is a Doris Lessing scholar, came across a reference to North’s journal in WorldCat. It wasn’t the original manuscript but a 19th-century handwritten transcript that was kept in the Huntington Library in California. We got a copy, and that led to our finding the original at Lambeth Palace Library in London. We also found a copy of it from Shakespeare’s time at the British Library in London.

In your opinion, why didn’t North get fame and glory for, as you argue, writing plays that Shakespeare later adapted?

North got a lot of praise for his work as a translator, but not as a playwright. If you want to find references to his ability as a playwright, you have to turn to the satirical literature of the time. There, you find literary critics talking about him but not naming him. But as you assemble his life, you realize they’re talking about North. Also, there are records of payments being made simultaneously to North and the Earl of Leicester’s theater company, leading us to believe that North was being compensated as a playwright. But what we call the smoking gun is all of those parallels that we find in the writings.

The problem is that nearly all plays from this time period, including North’s, are gone. Later in the century, it became conventional to publish plays. But in the mid-1500s, when North was writing, theater was an ephemeral experience. Scholars estimate that no more than one-sixth of the plays that existed then exist today. But we can look to the early modern period for references to lost plays, including many with titles or plots that strongly suggest that earlier versions of Shakespeare’s plays did exist. The challenge, of course, was to prove our claim without having the major piece of evidence. But in cobbling together other kinds of evidence—including the fact that Shakespeare was borrowing from North’s travel journal before it was published—I believe we have made the case.

With your co-author living in New Hampshire and you in Pennsylvania, how did you make the collaboration process work?

We exchanged everything by email. Dennis was the digital researcher. He used various databases—like Early English Books Online (EEBO), Google Books, and Google—to look for certain phrases and passages appearing in various works. I was the archival researcher, tracking down the manuscripts and information concerning their provenance. I wrote the chapters on the manuscripts, and Dennis did the interpretive work on Henry VIII and The Winter’s Tale.

How critical was the role of technology in helping you substantiate your findings?

There would be no way to determine all of this through the traditional methods of source study, which would require having the two texts side by side, and then visually finding the similarities. All of the surviving writings from the early modern period are in the EEBO database. Dennis would type in a phrase that North used and get the result of two texts that use that phrase: one by North, and one by Shakespeare. More often than not, we found that no other writer in the early modern period had used that phrase. That tells you something.

What do you think these findings say about Shakespeare, and how do you think the Shakespearean community will respond to them?

We do not anticipate easy acceptance. There are those who will insist that our case cannot be proven without North’s plays. But even without them, the evidence is strong. And digital searches of the massive online databases yield so many instances of borrowing that Shakespeare’s indebtedness to North simply cannot be denied. When we published our 2018 book, the media played up the fact that we were using plagiarism software and took that to mean we were accusing the Bard of plagiarism, a word that didn’t exist in Shakespeare’s time. In fact, it was quite common for one playwright to borrow from or collaborate with another. Do such objections cast a shadow on Shakespeare’s brilliance? Not for us. We do not believe that our discoveries in any way tarnish the reputation of the world’s most celebrated playwright. Rather, our work shows what a consummate man of the theater Shakespeare was, how shrewd and smart. The Folger Shakespeare Library, the Shakespeare Institute, the town of Stratford-upon-Avon, and Bardolatry worldwide all endorse Shakespeare’s genius. We do not believe we have disturbed that image. But we have amended it: Shakespeare was a genius not at writing plays, but at adapting them.

Charles A. Dana Professor Emerita of English and former Lafayette provost

Charles A. Dana Professor Emerita of English and former Lafayette provost