Michiko Okaya reflects on her 40 years of curating a collection and bringing galleries to life

By Stephen Wilson

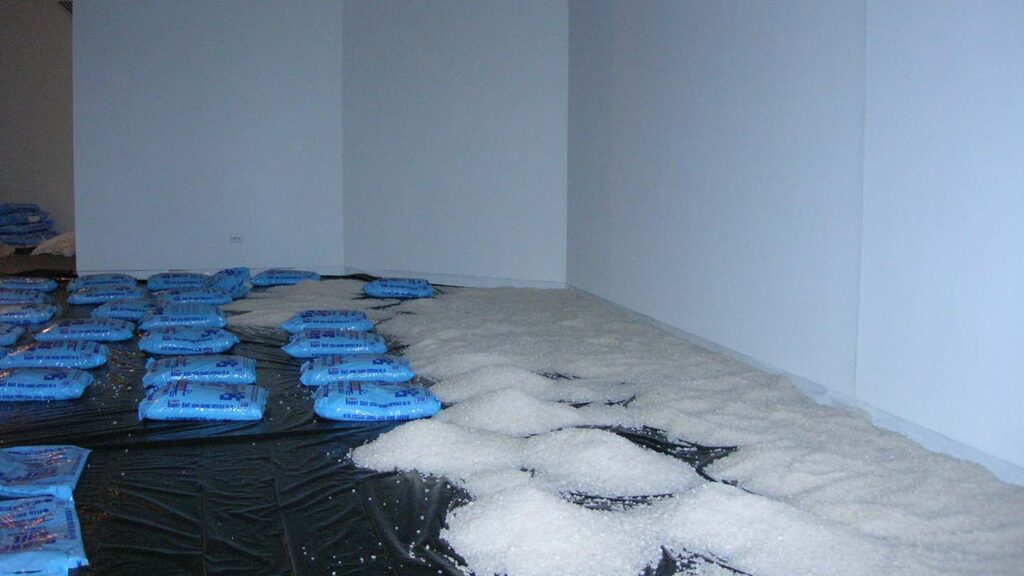

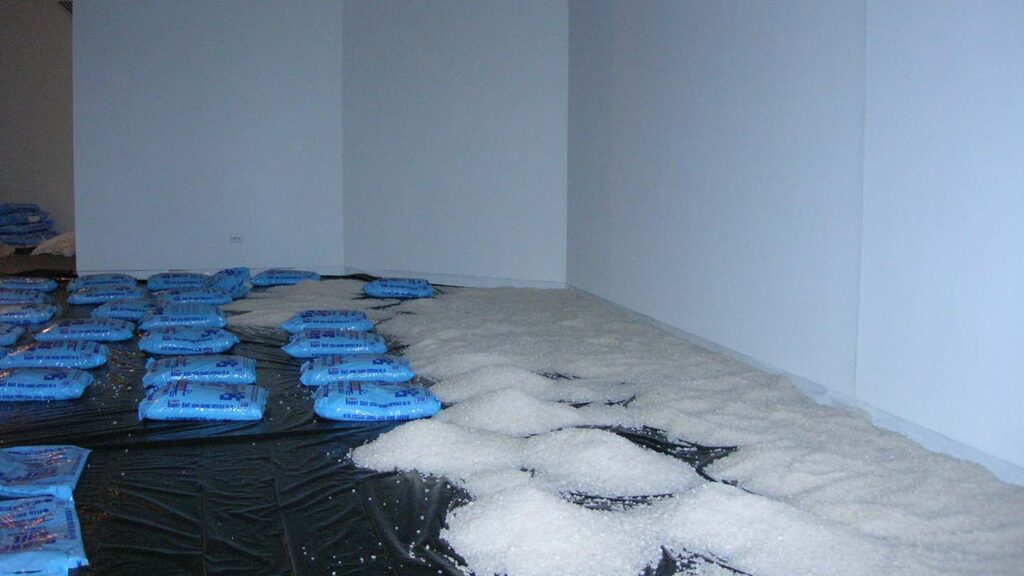

Michiko Okaya, director of art galleries and collections curator, is on the phone with the Lafayette plant operations (now facilities) team. She needs salt. It’s not to deglaze the sidewalks outside Williams Center for the Arts but rather to cover the floor of the Williams Center Gallery.

She is working to fulfill an idea by theater director, choreographer, video and installation artist Ping Chong with Tony Jannetti for his exhibit, Testimonial II, presented in conjunction with Ping Chong and Company’s performance of Undesirable Elements in 2006. When he started his sentence with, “I have an idea…,” she thought, “Oh sh*t,” but what came out of her mouth was “Sure!”

“Sure” is a simple phrase, one laced with equal parts willingness and acquiescence—a phrase often uttered when working with artists, curating experiential exhibits, and managing collections.

The rock salt plant ops could lend to the gallery had impurities, fine for snowy roads but not what the artist wanted. He wanted pure white salt crystals. The performance was about preserving memory with the salt acting as a preservative. Plant ops directed her to the local farm bureau office. The result was more than 100, 40-pound bags of solar salt, glinting in the theatrical lighting.

Filling the gallery with salt for artist Ping Chong

Would you accept a collection of Danny Lyon photographic prints? Sure.

Can you accommodate a class tomorrow wishing to view works from the Italian Renaissance? Sure.

Might we cover the floor in pounds and pounds of salt (and later a truckload of topsoil)? You guessed it.

Such has been Okaya’s role for the last 41 years … almost 42 now, as the pandemic made forming a search committee nearly impossible. So Okaya continued her steady stream of sigh-laced willingness last year. The only difference was those “sures” hailed from remote locations.

Remote locations, though, are one of Okaya’s specialties.

When she began in 1979, the College’s art collection was primarily managed by plant operations. In some way it made sense. Art hangs on walls, and plant ops oversees what happens to walls, so plant ops did the moving, and hanging, and keeping of inventories. The collection was stored in available spaces (née closets, drawers, and attics) in various administrative and academic buildings.

By 1982, management of the collection was turned over to Okaya.

Soon after, she saw the plans for what would become Williams Center for the Arts and was surprised to see nothing in the way of proper art storage. As she inquired and explained, she earned a consolation prize: Most of the collection was consolidated, first in the attic of Pardee Hall and then, to the basement of Kirby Hall of Civil Rights.

Speaking at opening night of the art study center

But the Kirby basement posed issues with climate—both fluctuations in humidity and cascading water during heavy rainstorms that rivered down steps, across the floor, and threatened to seep beneath the door jamb. (The floor in archives across the hall was pitched a tad lower, and water usually flowed there.)

The collection sat there until 1997. The limited space served as a mild growth deterrent. When Kirby Hall renovations began, collection storage was moved to the Kirby attic.

It was an upgrade sans water and with climate control and security, but the room wasn’t large enough to host researchers or easy enough to find to invite classes. So Okaya was resigned to do as she had done for years—make a catalog of available art and safely schlep it across campus to requested locations. Moreover, it allowed her to focus her attention on the gallery.

When she began her role in planning exhibits, it was fairly common to print an announcement, hang shows, host a talk, and then press repeat—next show and talk, show/talk, show/talk.

But Okaya’s aspirations were greater: to make the gallery less of a place of beautiful and quiet isolation and more of a gathering space for interdisciplinary engagement.

“At an institution of Lafayette’s size, it is possible to have a better idea of what interests the faculty and students and reach out to find artists who help transform the gallery into a space filled with cross-campus opportunity,” she says.

Case in point: Martha, the dead passenger pigeon.

Named for First Lady Martha Washington, Martha was the last known living passenger pigeon in captivity. A celebrity at the Cincinnati Zoo, Martha’s demise came in September 1914—several years after her mate, George. Her death marked the extinction of the species Ectopistes migratorius. Okaya planned a semester-long remembrance, as part of the national Project Passenger Pigeon program.

“I wanted something more engaging than a room full of dead bird images,” she says.

What ensued was visual artist and musician Michael Pestel’s REQUIEM, Ectopistes migratoriu and Catalog of Extinct Birds, an evolving multimedia exhibition that became the nexus of a campus-wide festival of knowledge and talents, including theatrical readings, musical performances, dance, spiritual eulogies, and lectures from faculty and guests on animals in literature, genetic code of birds, saving birds from window strikes, and the philosophical ethics of de-extinction. She also suggested Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction as a choice for the 2014 summer reading book for first-year students.

Okaya curated other shows like this one that likewise included a full cavalcade of spectacle on the Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927 with Alison Saar’s exhibition Breach, in 2016. Addressing issues of race, gender, and spirituality, Breach was the culmination of Saar’s creative research on American rivers and their historical relation to the lives of African Americans. The exhibition was installed in the Williams Visual Arts Building’s Grossman Gallery, a block from the Delaware River and situated above Bushkill Creek—bodies of water that had flooded a decade earlier.

“The gallery exhibit can take artwork out of a silo and weave it into other disciplines, and deliver new ways of looking at broader issues,” she says.

That show also involved a “sure” from Okaya. How about using water and mud from the Bushkill Creek and some pigment to stain gallery walls to indicate the high-water mark?

Gallery show for Alison Saar’s exhibition Breach

Exhibitions also have complemented summer reading selections:

In 2008, the summer reading book was Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma. In the associated “Corn on the Quad” project, three plots of modern, industrial varieties of corn were planted on the Quad. At the Williams Center, she planted a complementary plot of four open-pollinated heirloom varieties. Harvested ears of corn were then incorporated into the exhibition Nature (Re)Made, Genomics, and Art. Organized with artist Elinor Levy, the exhibition addressed just a few of the issues raised by the genomic revolution and was presented in conjunction with Liz Lerman Dance Exchange’s performance of Ferocious Beauty: Genome. Like Lerman, the artists in Nature (Re)Made conducted explorations that revolved around genetic research and raised questions in such consequential areas as the environment, health care, and privacy.

Corn at Williams Center for the Arts as part of “Corn on the Quad” project

For Passing Bittersweet, the interim 2020 exhibition, guest curator Elizabeth Johnson selected works by artists that echoed poet and essayist Ross Gay ’96’s conviction that numberless, small, positive human actions and transactions dispel what is dark, lonely, and unjust. Gay’s book was the 2019 summer reading book.

The same can happen when the show is less about a topic and more about an artist.

Take Ping and his salt.

Or biologist and artist Brandon Ballengée. The installation of his photographs of Charles Darwin’s research pigeons was coupled with numerous environmental science lectures and “eco-action” experiential nature walks.

Okaya’s approach to visiting artists has been to provide them a space to experiment. She believes an important role of the academic gallery director is assisting artists and curators to explore ideas and media.

“If they were selling work in a commercial gallery, it can be nice to have room to explore new ideas that may not be as commercially viable,” she says.

So she would encourage them to show works they had never shown before.

“One of the advantages of being an academic gallery here at Lafayette is that we don’t depend on admission fees or number of visitors,” she says.

Take William Wegman’s show Instant Miami, which hadn’t been on display since 1985, Stacy Levy’s Blue Lake, or Jim Sanborn’s Looted exhibit and his “Kryptos” lecture.

Another standout and a favorite of Okaya is Fluxus/intermedia artist Larry Miller, whose exhibit and performance had a student sorting through bags of carrots for ones that met his specific criteria, including “good shoulders.” Miller then installed them by nailing a 14-foot-long row of the vegetables to the Williams Center lobby wall for the work Line. Robert S. Mattison wrote in the catalog essay for Miller’s 2001 exhibition Dream/Don’t Dream, “By its use of organic material, Line opposes the notion of permanence in art and more particularly the cold metallic geometry of minimal art that dominated the 1970s. In contrast, Line measures the passage of time as the carrots shrivel and decay on the wall. Yet, paradoxically, as the carrots decompose, they become visually more lively, beginning to twist and turn until, in the artist’s words, they ‘look like dancers.’”

Larry Miller installing carrots in Williams Center lobby

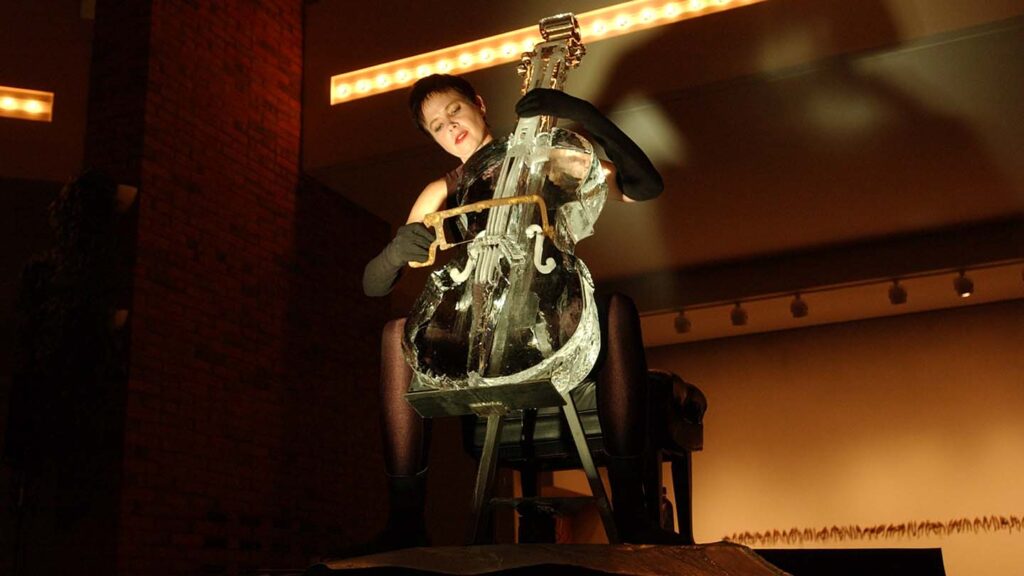

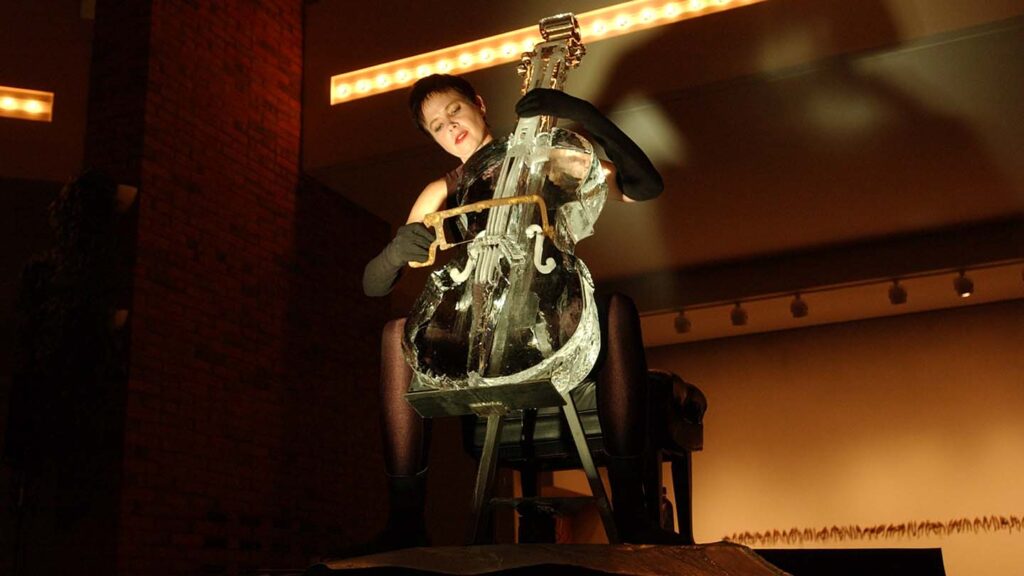

Line was visible in the background of cellist Joan Jeanrenaud’s visually and aurally stunning performance Ice Cello. She “played” a cello-shaped block of ice in the lobby of Williams Center. The percussive sounds of the varied bows she used to slap, scrape, and “bow” the cello, and noise of water dripping from the melting ice sculpture, were manipulated by sound artist Gregory Kuhn. Her performance was a remount of Charlotte Moorman’s Ice Music for London, created by artist Jim McWilliams in 1972.

Cellist Joan Jeanrenaud’s performance Ice Cello

All of this work culminated in something wonderful for Okaya as Williams Arts Campus at the base of College Hill dramatically altered the arts landscape at the College. With many departments’ footprints being reshuffled, space opened up in Williams Center for the Arts, and plans were drawn up and approved for an arts study center.

“The news of it nearly knocked me over,” she says.

After decades of lobbying for accessible art storage, finally a place to store, display, and host. Its construction coincided with the gift of the Goodman Photography Collection, over 1,200 prints from notable photographers, including Henri Cartier-Bresson, Arthur Rothstein, and Danny Lyon. Superb examples in the Kirby Collection of Historical Paintings can be easily viewed from the adjacent study room.

Dedication of the Kirby Art Study Center finally brought together more than 4,000 works in the College’s collection that, as Okaya said that night, “makes accessible for the first time the rich artistic resources not already on display across campus and provides a modern museum-standard environment for the care, display, and study of our growing art collections.”

The collection’s growth will be in another’s hands when Okaya can truly step away, but space for that growth is now possible. As she looks back, as is common at this point in a career, she sees more to do.

“It’s easy to reflect on where you have come, but easier still to see all that has yet to be accomplished,” she says.

1 Comment

Michiko Okaya brought Lafayette’s Art

Collection into the modern era of stewardship, professionalism, museum level presentation and curatorial awareness.

She made it possible to accept artworks for the collection by establishing our ability to care for significant gifts.

Michiko is the consummate professional. She was able to work with faculty, students and administrators to produce exhibits of pedagogical significance. Her carefully planned shows were notable for their range of regional, contemporary, historical and global art.

Michiko worked with artists of all genres to bring out their best. Her patience, kindness and humanity brought forth collaboration and participation from all corners of the campus as well.

She increased the availability of primary sources from which one could teach and her leadership put our collection on the map. Michiko will be missed. Congratulations on an amazing career!

Comments are closed.