Anthropologist, author, filmmaker Christal Whelan to speak about Japanese religion and culture April 13

By Stephen Wilson

In 1995, a few Japanese men in their late 90s, the last remaining Hidden Christians on the Goto Islands, prepare for Otaiya. Translated as big evening, Otaiya is the secret word to describe Christmas Eve. The men recite prayers and prepare for a communion service of rice and sake. This ritual, hidden out of fear for nearly 400 years, is being filmed, a veil lifted so the ritual is not lost forever as the men journey closer and closer to the end of their lives.

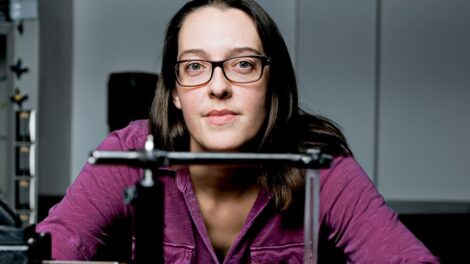

Christal Whelan

Behind the camera is Dr. Christal Whelan, a scholar dedicated to anthropology and religion, and the 2022 Earl A. Pope Guest Lecture in Christianity Around the World.

The annual guest lectureship is sponsored by the Earl A. Pope Memorial Guest Lectureship Fund, and supported by the Lyman Coleman Guest Lecture Fund, both through the Department of Religious Studies.

Pope was a minister for a decade before joining the faculty of Lafayette College, where he taught in the Department of Religion for the next 30 years while routinely traveling around countries behind the Iron Curtain, under the domination of the former Soviet Union, as a specialist in the study of various persecuted minority religious communities there.

The lectureship, unique for an undergraduate institution, brings distinguished speakers each year who represent different world regions, including Africa, Latin America, South Asia, and East Asia.

Whelan’s lecture is titled “From Persecution to World Heritage: The Loaded Legacy of Japan’s Hidden Christians,” and will be delivered on Wednesday, April 13, 2022, 7:30-9 p.m. in the Marlo Room on the second floor of Farinon College Center.

How did you feel about being selected to deliver the Pope Lecture?

I was honored and surprised. I have had such a varied and nontraditional career and path in my life that it was flattering to be chosen.

Tell us a bit about your scholarly trajectory.

As an undergraduate at Harvard, I fell in love with Dante’s Divine Comedy and wanted to go to Italy in order to learn Italian and devote myself to a life of Italian letters. I spent time in Padua, at the university there. But during my master’s in Italian studies at Brown, I began to take an interest in Portuguese. I earned a scholarship from the Portuguese and Brazilian studies department and went to Lisbon for a summer. While there, I discovered an ancient connection between 16th-century Portuguese missionaries and Japan. The more I explored the topic, the more it became an area I felt compelled to study. It shifted me from a linguist and literary scholar to an anthropologist and fieldworker. Soon I went to Japan.

Japan is where you discovered the subject for your talk.

At a Jesuit university in Tokyo, I was looking at copies of old missionary texts when I came upon a photo of a Japanese baptism. Photography is a modern medium, which meant that the ceremony was likely to have been sometime in the early 20th century. That photo stunned me because Christianity was outlawed in Japan in 1614. Those who remained Christians faced horrible tortures to force them to denounce their faith. Japanese Christians were also made to participate annually in the fumi-e, a ritual where individuals would be asked to trample on treasured Christian images and objects. This marked the beginning of a tradition of camouflage. These beleaguered converts began to hide their identity as Christians since being a Christian was a crime punishable by death. Japanese leaders had groups of five families within communities monitor each other. This just increased the pressure to hide their faith and any evidence—rosaries or religious images. So there could be no pooling of talents or building of churches for communal worship. It was isolating, and that’s what it was meant to be. This is the backdrop of a tradition which became very bare, pared down to rice and sake communion and prayers transmitted from each generation to the next. This system of severe repression remained in place until the late 1850s when Japan began to reopen its ports to trade and outside influences. But Christianity was still against the law until 1873.

What happened in Japan when Christianity was no longer outlawed?

Many secret Christians revealed themselves, coming forward and formally becoming members of the Catholic faith. But some did not join or even identify with the Catholicism they encountered in the 19th century. Instead, they preferred to continue with their own customs as they had long developed in secrecy. It’s important to remember that these underground Christians didn’t have biblical knowledge. The Bible had not been translated into Japanese at this point. What they did was to put together fragments of stories, blending their own tales with Christian narratives, legends, and some doctrine. It was the hidden Christians, who wished to remain hidden, who became the subject of my documentary film, Otaiya: Japan’s Hidden Christians.

Christal Whelan in Kyoto in front of a Buddhist temple gate along the Tetsugaku no michi or Philosopher’s Path

Is this what your lecture will cover?

This background is important, but my lecture will talk more about the 2018 decision to enlist several hidden Christian locations in and around Nagasaki as a composite UNESCO World Heritage Site. I stopped my work on the Hidden Christians around 2000. It was too sad to watch a religion dying, so I moved on to study the growth and energy of new religious movements in Japan. But I deeply understand and have a tangible record of the traditions that have been lost. Today, the sites are being spiffed up; glamping and boat tours have moved in. There seems to be an erasure of some vital pieces of the full historical narrative, which is pretty appalling. In coming to terms with this situation, I have tried to understand the stakeholders and the process of World Heritage inscription.

Your history is tied to Pennsylvania.

I was born in Pennsylvania. My father was a surgeon assigned to the U.S. Army Hospital in Valley Forge. He was a war wounds specialist who served in a MASH hospital during the Korean War and later wrote the U.N. guidelines on treating war wounds. As I understand it, the Valley Forge Army Hospital was established to care for and rehabilitate men wounded in war. I trace my ease of going from culture to culture to him. We moved to Germany after I was born, and I spent most of my childhood years in Hawaii, a state not like any other in the U.S. Most of my school teachers growing up were Japanese Americans who taught us Japanese dances, and to love things like li hing mui (which is actually Chinese). My mother didn’t want us to grow up too parochial, and so insisted on taking us to different Buddhist and Taoist temples on Oahu where we lived. I think I was coerced into anthropology based on my exposure to so much diversity growing up. I wanted to better understand it.

Your life sounds like an embodiment of liberal arts.

Liberal arts is an important approach to education. Our country seems to be moving to such a utilitarian way of thinking. The value of liberal arts is that it develops people with a broader perspective and framework, which, at least potentially, opens up more of the world to a person. Those shaped by the liberal arts seem to be self-starters and to enjoy their lives more. This leads to more creativity and more engagement. The world can be fairly mute if a person lacks the basic tools to approach it creatively. And these tools are amply provided by a liberal arts education.

How do you see the liberal arts impacting your life today?

I suppose it informs the choices I make in my life. I value poetry, languages, history, art, and religion. They are part of my daily life. Right now, I am building a very small and sustainable house. Living in Japan got me used to tiny spaces, so I got the idea that I should eventually have a tiny house. I went to tiny house fairs on the East Coast, and even went to test one that had been set up at a campground in New York state for this purpose. I now have a 4-acre parcel of land, had an artesian well dug, installed a septic system, and the construction of this very small house is now in full swing. One whole wall—floor to ceiling— is for books. Solar panels are in the near future. I have to admit that it is a lot of work to make every decision intentionally. But I have moved so many times all my life that I have kept my belongings whittled down … except for books. I sold 1,000 when leaving Japan!