New course connects agriculture, food, and geology in Italy

Eighteen students spent three weeks in Italy learning how location, climate, soil, and topography all play a part in “terroir”—or “the taste of place.”

By Shannon Sigafoos

The last time you ate “farm to table,” did you think about how the geography of the land your food came from ultimately affected how that food was grown?

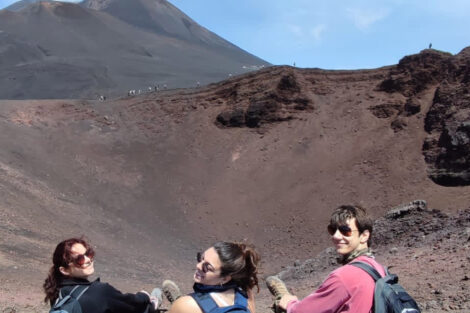

As 18 students found out this summer, location, climate, soil, and topography all play a part in “terroir”—or “the taste of place”—suggesting how food and drink are geographically and culturally specific. For three weeks, they traveled throughout Italy, from Sicily and Naples in the south, through Rome, and into the fertile Tuscan region, experiencing active volcanoes, organic farms, food movement organizations, and socially active culinary institutes along the way.

The first-time course was led by Tamara Carley, associate professor of geology, and Benjamin Cohen, associate professor and chair of engineering studies, who wanted to combine their interests and teach how agriculture and geology are intimately connected.

“My first book was about the history of agricultural chemistry, where I found that geologists, agricultural chemists, and farmers were all the same people. That seemed like an easy start, and we do have overlaps,” explains Cohen. “I’ve always been fascinated with layers—the physical layers, conceptual layers, cultural layers, and historical layers. So, this just sort of presented itself as a three-layered class of geology, agriculture, and food.”

“We actually had several students in the class who had been to Italy before, and it was fun to see them discover this landscape in a new way for the first time. We were getting into questions of, ‘Why is this mountain here?’ or ‘Why is this rock here?’ or sharing ‘What a great place to have a fortified community,’” says Carley. “Where there were volcanic caldera lakes, there was a great freshwater fishing resource. There became things you could point to, as to how civilization was established there, or why it was such a prosperous area. We were able to make connections that people hadn’t thought about before.”

As the group made its way throughout the country, students kept field notebooks documenting observations and analyses of each location and activity, and completed readings and response papers, a midterm exam, and a final capstone portfolio.

In Taormina’s Etna vineyard, they learned how soil and geology affected food and wine production. In Gole dell’Alcantara, they experienced the Alcantara gorges, which are real canyons made of black lava walls up to 50 meters high, in the typical shape of a prism that the rocks take on during the cooling process. They climbed to the top of the active Etna volcano, studied the islands of Vulcano and Stromboli in the Tyrrhenian Sea, trekked over Rome’s Seven Hills, had a geologic guide of the volcanic Lake Albano, walked the Vesuvius crater, took a guided tour of Pompeii, learned about “short chain” Chianina cattle breeds and goat cheese production on organic farms, and more. Along the way, they ate an abundance of locally sourced meats, cheeses, and vegetables, and learned what areas were best for growing grapes for wine production and wheat to feed animals to make other foods.

“I believe I wouldn’t have appreciated and valued terroir as much in a traditional classroom setting. I was able to witness direct evidence of how the earth influences the food and culture. For example, we visited a winery on Mt. Etna and got to taste the different wines. We were able to taste the difference between wine from volcanic soil versus wine from the mainland. Without being at the winery and hiking the volcano, it would have been hard to fully embrace the idea of terroir,” shares civil engineering major Christina Ruvo ’23, who has always had an interest in geology and food studies. “One unexpected thing I learned about was the Slow Food movement. My family is Italian so I know how Italians take pride in their cooking and eating, but I had no idea how the Slow Food movement had an international impact. I never considered how impactful mono-cropping and fast food is to our society.”

“One of the most unexpected things I learned was the extent to which Italy’s food culture and systems differ from those of the US,” agreed Julia Banks ’23. “We visited many farms that were small and nearly self-sufficient, and had been for a long time. One that comes to mind is the goat farm we visited where they grew wheat to feed the goats and pigs and make the bread we were served. The pigs were also fed whey and other cheese-making byproducts so they did not go to waste, and ultimately the pigs were used to make sausages and other meat products while the goats were used for dairy products. This type of ‘short chain’ sustainable farming is far more common in Italy than in the US, where there are a lot more large-scale production farms.”

Cohen and Carley are hoping to hold the course again during the 2023-24 academic year, and are pleased that students connected to so many aspects of what they experienced in Italy—particularly, realizing how food, food culture, and issues of food justice changed from place to place.

“The first time we moved locations, the food in our first location, Taormina, was different from the food we had when we went out to the islands. And then the food changed again when we got to Naples, and the food there was different from the food in Rome. It was a real benefit of our course that we got to transition a lot,” says Carley. “Each of these places has discrete geology, food culture, and agriculture.”

Learn more

Office of International & Off-Campus Education

Lafayette College recognizes that we live in an increasingly complex and interrelated global environment, and connecting the classroom to the world outside our walls is at the core of the College’s mission. Off-campus study combines academic rigor with experiential learning through immersion in an international or culturally significant domestic setting.