Prof. Mónica Salas Landa to deliver March 25 Jones Faculty Lecture

By Bryan Hay

A little-known petroleum geologist from Texas who explored oil fields in Mexico is the inspiration for Prof. Mónica Salas Landa’s Jones Faculty Lecture, from noon to 1 p.m., March 25 in 224 Oechsle Hall.

A little-known petroleum geologist from Texas who explored oil fields in Mexico is the inspiration for Prof. Mónica Salas Landa’s Jones Faculty Lecture, from noon to 1 p.m., March 25 in 224 Oechsle Hall.

Edwin B. Hopkins (1882–1940) worked for the U.S. Geological Survey and later in Mexico for the Mexican Eagle Oil Co., focusing primarily on development of the oil industry in the district of Papantla in the lowlands of northern Veracruz.

As a sociocultural and historical anthropologist who has done ethnographic work on the environmental and socio-political effects of oil extraction in the area, Salas Landa, associate professor of anthropology, wanted to learn more about the development of the oil industry in Veracruz, so she conducted research at the National Archives in Mexico.

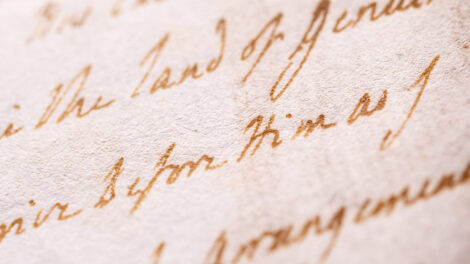

During her presentation, Rough Topographies: Grounding the History of Oil Extraction on Mexico’s Gulf Coast, Salas Landa will not only discuss Hopkins’ writings and images but also reexamine the notion that science, in this case, geology, is neutral.

She took time from her schedule to preview her talk.

How did you arrive at this topic? What inspired you to research Edwin B. Hopkins?

I came across Edwin B. Hopkins’ geological report while conducting archival research at the National Archives in Mexico, focusing on the development of the oil industry in the district of Papantla in the lowlands of northern Veracruz. It is in this area that one of the most important oil fields in 20th-century Mexico was developed in the 1930s: the Poza Rica oil field. This field was initially managed by the British and Dutch Royal Shell Group until the nationalization of Mexico’s oil industry in 1938. Therefore, Hopkins’ report is a piece of historical evidence that helped me better understand the earliest attempts to drill for oil in this region and the role that geology played in this process.

My interest in the history of oil development in Mexico was driven by my ethnographic work in the area. Before beginning my archival research, I had conducted ethnographic work in Poza Rica, examining how residents dealt with the presence of toxic and crude residues that the oil industry had left behind. Like many other industrial cities, Poza Rica has gone through the known cycle of boom and bust. Residents, in other words, have to deal with the effects of petrochemical pollution and industrial decay. What facilitated the transformation of the tropical forest into an extractive zone—a transformation that resulted in significant environmental destruction as well as social, political, and cultural changes? As a historical anthropologist, that was the question I brought to the archives.

Describe how Hopkins’ petroleum explorations led to the destruction of towns in Mexico. Why isn’t he a more widely known figure? Why is it important today to recognize and be aware of Hopkins’ oil discovery exploits?

Perhaps Hopkins is not a widely recognized figure, but by 1918, when he visited northern Veracruz, geological surveys had already become quite common and were crucial for economic purposes. It’s important to remember that the goal of these surveys was to assess the economic value of land and encourage expansion into resource-rich areas. Therefore, it was the report’s commonality, rather than its uniqueness, that made this piece interesting to me. Ultimately, what Hopkins’ report revealed was how geologists at the time conducted their fieldwork, which features of the material landscape they deemed important, and how these features were described and considered necessary to photograph.

This is significant because, as many scholars have documented, geology, through its practices, descriptions, and ways of seeing, has been closely intertwined with extractivism and fossil fuel capitalism. Therefore, engaging with geological materials and epistemologies appeals to anyone interested in the development and impacts of oil extraction.

What do you hope attendees will take away from your presentation?

An issue not just in geology but across all STEM subjects is the frequent portrayal of science as apolitical, with little acknowledgment of the influence or relevance of social relations and history. I hope attendees will first question that premise—”no geology is neutral,” as geographer Kathryn Yusoff argues. The subterranean knowledge, whether deemed “scientific” or otherwise, that we produce or fail to recognize, carries political, social, and environmental implications. The knowledge produced by figures like Hopkins, for example, has played a significant role in the development of fossil fuel capitalism, which has led to environmental degradation, primarily in extractive zones like northern Veracruz. Yet, as feminist geographers assert, topographical and geological knowledge can also be leveraged to challenge and counteract these forms of exploitation and ruination. This is the second point I hope attendees will take away from my presentation.

Free and open to the public, Salas Landa’s talk is sponsored by the Thomas Roy and Lura Forest Jones Faculty Lecture and Awards Fund, established in 1966 to recognize superior teaching and scholarship at Lafayette College.