By Bill Landauer

A man looks at you from a photograph as he extends a toy alligator to an impeccably dressed trio of children. The children recoil and raise hands to their faces in mock horror. On a sign in the photo, an arrow points to the scene. The sign reads, “Scary.”

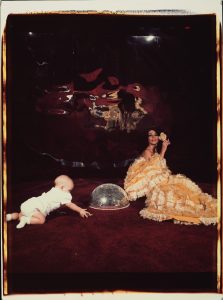

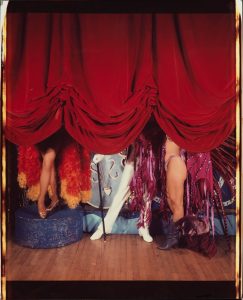

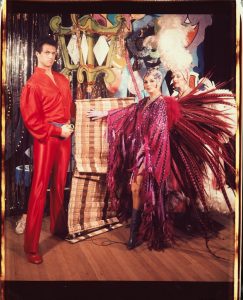

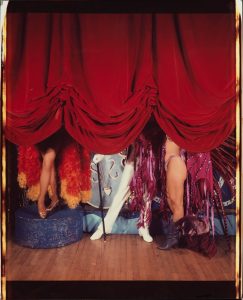

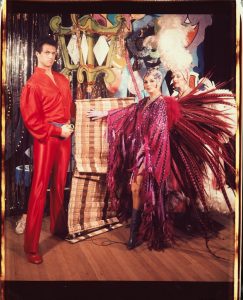

Other photos in the exhibition show incongruous juxtapositions—a man holding a fan seated on a wall at the beach, seemingly oblivious to the costumed cabaret dancers striking a dramatic pose next to him; a couple stands in front of a stone wall holding a similarly colored window shade, the same shade is a prop in a tableau set inside Les Violins nightclub with exuberantly dressed performers. Closer examination of the photos raises questions: Is that a kiddie pool? If so, why? Whose foot is it? Why is he holding a roll of duct tape?

‘Child’s Play’

Maybe William Wegman’s Instant Miami exhibit won’t say much about its namesake city to you. But to artist Nestor Gil, assistant professor of art, the exhibition touches a side of the city seldom captured in photos.

“Miami,” Gil writes in his catalog essay, “with all its efforts towards high culture and cosmopolitanism, yet still replete with evidence of just how far from these ideals it remained, is the backdrop shared by all these images. How can an image be at once hilarious and seedy and familial and alluring?”

Co-curated by Gil, Instant Miami, a series of 22 20-by-24-inch Polaroids shot by the artist, will be on display through Dec. 8 at the Williams Center Gallery located at Williams Center for the Arts, 317 Hamilton St. The photographs have not been shown since 1985.

Wegman will visit campus for an artist’s talk, book signing, and reception 4:10-6 p.m. tomorrow. The talk will be in the Gendebien Room of Skillman Library, followed by the signing and reception at the Williams Center.

Wegman will return Monday, Oct. 29, with John Reuter, director of the 20×24 Studio, to talk about the Instant Miami Polaroid project. Reuter worked with Wegman on nearly all of his Polaroid projects, starting in the late 1970s. The conversation takes place in the Williams Center at 4:10 p.m. in seminar room 108. A reception for Wegman and Reuter will follow in the lobby.

‘Opening Act’

The exhibition and related programs are free and open to the public.

Wegman’s work is also featured this fall in a trio of exhibits on the main floor of Skillman Library. Included are images of his Weimaraners with classic mid-century modern furniture (2015); images of the dogs taken with his large-format 20×24 Polaroid camera (1995-2005); and an artist’s book, created in homage to his beloved Maine and inspired by his extensive collection of camping books, nature guides, and Boy Scout manuals, Field Guide to North America and to Other Regions (1993).

Wegman’s photos of his Weimaraners had already become famous by 1984, when he was invited by University of Miami’s Lowe Art Museum to visit Miami.

Wegman was, in his words, “between dogs.” Man Ray, his video and photography muse, had died two years earlier. (He returned to photographing dogs with Fay Ray and her offspring several years later.) Making Instant Miami, says Wegman, “was really a good thing for me. I think it forced me, challenged me, in some ways to not use the crutch of the dog.”

The Miami assignment was to view the city through the eyes of an artist. He was invited “to see, to react, not to document.”

‘Inferno’

He spent a week, primarily in three locations: South Beach, Grove Isle, and Les Violins, the Cuban cabaret-style lounge in Little Havana that was all the rage among Miami Cubans—a swanky night out for a special occasion.

With the performers’ enthusiastic participation, Wegman settled into photographing them for most of the duration of his time in Miami. “Les Violins turned out to be great for many reasons,” says Wegman. “The cast, the sets … It was really a treasure to find that. And everyone loved working on this project. ‘We are making history!’ one of the performers said.”

Wegman used the 20×24 Polaroid camera in Florida. He found the large format camera oddly inspiring. “Lugging this obscenely large, not very cooperative camera to extreme locations—it’s formidable.” This Polaroid was described as an “instant” camera. But this was not the popular small hand-held, easy-to-operate Polaroid camera whose white-bordered 3.3-by-4.3-inch photos had been imprinted upon our culture’s imagination as an “instant” photograph. The camera Wegman used in Florida was refrigerator-sized. It was one of only five made by the Polaroid Corporation, and it had been specially flown from New York to Florida for this shoot. Setting up the large camera for a shoot was not quick. It required assistants to move it and set up strobe lighting, and a Polaroid technician to operate its finicky mechanics.

The unique 20×24-inch image did develop within minutes—“instant” in an era when photographers had to process film and print in a darkroom—and allowed Wegman to react immediately to recompose and improvise. The 1984 Lowe Art Museum’s press release described his work process: “Watching Wegman work was something akin to watching improvisational theater. He interacted with places, props, people. Strangers were consistently willing to get in the pictures, and the artist listened to them.”

‘Blind Ambition’

“The photographs possess a richness and immediacy, framing, and sense of light and color—the formal details of making a great photograph—long associated with this artist,” Gil says. “They also provide evidence of his wit, establishing contexts for the wry and ridiculous constructions of people, objects, materials, and space with which Wegman populates them.”

Text of Gil’s essay in the exhibit catalog can be found on the gallery website.