Notice of Online Archive

This page is no longer being updated and remains online for informational and historical purposes only. The information is accurate as of the last page update.

For questions about page contents, contact the Communications Division.

In her new book, Prof. Carrie Rohman writes that creativity is not exclusive to humans

By Kathleen Parrish

By Kathleen Parrish

In 2005, Carrie Rohman’s two worlds collided when she attended a six-week course at Cornell School of Criticism and Theory. There, the associate professor of English was introduced to the idea that the same creative forces inspiring humans to make art exist in animals.

The notion was revelatory to Rohman, who had always drawn a line between her work in animal studies and her life as a professional dancer and choreographer. These disciplines, she believed, lived in different realms. Plus, she didn’t want to write about dance, she just wanted to dance, or so she said. But what if her real reason for keeping the two separate was to protect the animal activity of dance or the “creatural way of being” from the constraints of intellectual analysis?

She decided to open her “intellectual toolkit” and take a serious look at dance—and other art forms—through an animal studies lens. The result is Choreographies of the Living: Bioaesthetics in Literature, Art, and Performance, in which Rohman explores the aesthetic impulse as an experience across species, a concept that challenges our relationship with animals, our understanding of art, and the notion of human exceptionalism.

When did you start dancing?

Starting at the age of 6. I was trained in very traditional forms: ballet, tap, and jazz. I had a vexed relationship with ballet. That culture was really oppressive. After high school, I thought I was done dancing altogether. I wasn’t exposed to modern dance until I went to college at the University of Dayton. Strangely, my first college roommate was a dancer. She said, “You need to audition for the Dance Ensemble.” After I saw and tried to learn modern dance, I soon realized this was the form I was meant to be practicing. Renowned choreographers from the Dayton Contemporary Dance Company used our ensemble as a testing ground for their work. By the time I was in graduate school at Indiana University, I was part of a small dance company in Bloomington. Later, in Cincinnati, I was on the teaching faculty at Contemporary Dance Theater, and performing and choreographing frequently. I always tell people dance is my avocation.

Why animal studies?

When I was in graduate school, literary scholars had not yet taken up animal philosophy in a serious way. I was interested in feminist literary theory and thought that’s what I was going to do. But then I started reading more emerging work in animal theory, and kept seeing that complicated ideas about animals were everywhere in modernist literature. After Darwin, humans’ relationship to animals—and to themselves—underwent a serious crisis, and literary scholars hadn’t explained that element of literary history. As a graduate student, plenty of people were asking, “What are you doing?” It was kind of risky, but now animal studies is an exploding interdisciplinary field.

Why is that?

We are an imperiled species and have come to realize that if we don’t see ourselves as part of the creatural life on this planet—instead of dominating and controlling it—things aren’t going to go so well. Climate change and the broad ecological crisis have certainly helped to get us more interested in what’s happening to all living creatures. Our ethical sensibilities are also evolving as we begin to understand what animals are capable of cognitively and emotionally, and as we pay more attention to animal experience and animal suffering. There’s also discussion around the idea of personhood and how it needs to be a legal and social category that also applies to non-human creatures, such as cetaceans like dolphins and whales. We never would have considered this 20 years ago.

How has your new consciousness within animal studies informed your relationship with dance?

In 2014, I did a movement and sound performance with Michael Pestel as part of an installation he did in Williams Center for the Arts on the death of the last passenger pigeon. It was a moment when my scholarship in animal studies totally informed my decisions about choreography and performance. I listened to recordings of bird songs and recordings of Michael playing music with birds as I was making decisions about the choreography and structured improvisation. He’s a musician and installation artist, and he created this instrument that sort of mimics but also becomes bird sounds. As part of my creative process, I would go to the rehearsal studio in 248 North Third Street, listen to his recordings, and try to intuitively create a structure that would respond to the installation.

What do you want readers to take away from your book?

I really hope that people come away seeing art as a more than human force in a way that both enriches our views of humans and animals. The view of all beings should be elevated and complicated.

Three Things

“Tutu Chicken” by Rosemary Geseck

“Tutu Chicken” by Rosemary Geseck

When I was on research leave during the 2016-17 academic year, I started taking painting classes, something I’ve always wanted to do, but which felt especially important since I was writing a book about art. I took my first class at Baum School of Art with a teacher named Rosemary Geseck. She paints everything but specializes in painting animals, sometimes in whimsical and referential ways. I knew I was in my perfect first painting class when I saw this particular painting of hers, and I had to buy it. I told her that it sort of encapsulated the main ideas in my book project, and I now have it in my college office.

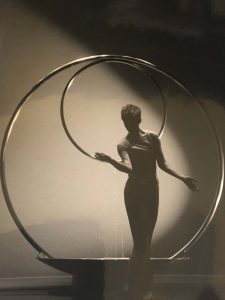

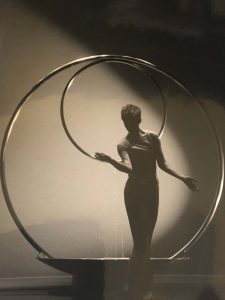

Dancing at Aronoff Center for the Arts in Cincinnati in 2000.

Dancing at Aronoff Center for the Arts in Cincinnati in 2000.

I was performing a piece that I had choreographed in honor of my father, who was terminally ill at the time. It was called ‘Knowing What You Have’ and paid homage to his remarkable influence on my life. The sculptural fountain in the background was designed and forged specifically for the piece by a friend of mine, Jeni Engel-Conley, who is an artist, designer, and dancer. In fact, she also danced in the piece.

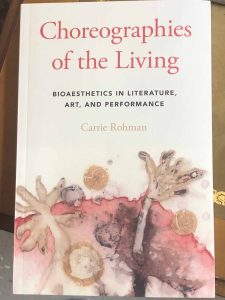

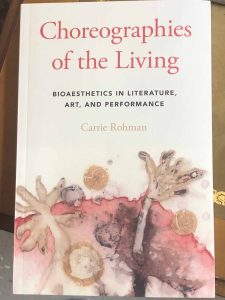

Cover illustration of Choreographies of the Living by Jim Toia, the art department’s director of the community-based teaching

Cover illustration of Choreographies of the Living by Jim Toia, the art department’s director of the community-based teaching

A few years before the book was finished, I kept seeing Jim Toia’s jaw-dropping spore drawings. They are transfixing and magical, and I realized also that they are absolutely bioaesthetic images— they capture the forces of beings in evolutionary processes, and the beauty and power of those forces. I approached him about negotiating with Oxford UP to have one of his images on the cover, and he sent me a few to consider. I could not take my eyes off this particular one. I was, and still am, completely honored to have Jim’s exquisite bioaesthetic image, “La Isla Roja” (2014), on the cover of this book.

By Kathleen Parrish

By Kathleen Parrish

Dancing at Aronoff Center for the Arts in Cincinnati in 2000.

Dancing at Aronoff Center for the Arts in Cincinnati in 2000. Cover illustration of Choreographies of the Living by Jim Toia, the art department’s director of the community-based teaching

Cover illustration of Choreographies of the Living by Jim Toia, the art department’s director of the community-based teaching