By Stephen Wilson

Her body is fused with rock—arms protruding from a square-cut Incan stone. In another image, the rock seems to smother her face and torso as her arms and legs splay from both ends of the slab’s surface.

Sculptural photographs in Karina Aguilera Skvirsky’s work mine her experiences as an Ecuadorian, Jewish American woman. That work is being recognized this year as the associate professor of art has earned two creative awards—$50,000 from Creative Capital and $25,000 from Anonymous Was A Woman (AWAW).

The art she’s creating blends photography, video art, and performance and has taken her on a trajectory that started with her 2015 Fulbright Award. She had made a film that traced her Afro-Ecuadorian great-grandmother’s roots as she traveled in 1906 from a mountain town in Ecuador to a coastal city to find work as a domestic.

“I reenacted that journey, following a path probably created by the Incas,” says Skvirsky. “While making that film, I learned about Ingapirca.”

“I reenacted that journey, following a path probably created by the Incas,” says Skvirsky. “While making that film, I learned about Ingapirca.”

Ingapirca is the largest Incan archaeological site in Ecuador. It is much smaller than Machu Picchu in Peru but uses similar architectural techniques.

The site was formed from precisely cut square stones mined close by. The Spanish repurposed many of the Inca and Cañari structures to build the colonial city of Cuenca, which is close to Ingapirca.

“The stones form the foundations of buildings in Cuenca and the structural outlines of the ancient site,” she says. “Cut perfectly and held together using no mortar, the stones can baffle historians who wonder how ‘primitive’ indigenous people could make such wonders without the use of modern tools. Some credit alien life forms. It’s insulting to my ancestors.”

Those stones and the Inca Trail have become her subject matter. In addition to the film, she created several series of photographs, including one that embeds historical images with images from her journey.

Those stones and the Inca Trail have become her subject matter. In addition to the film, she created several series of photographs, including one that embeds historical images with images from her journey.

These experiences inspired her current project, How to Build a Wall and Other Ruins.

“My thought, in our current political climate, was, ‘If Trump wants to build a wall, why not use Inca technology?’” she says.

She is making a film and works on paper that explore how the Inca people built their structures in order to think about histories and technologies that are forgotten over time. In the next few months, she will continue to conduct interviews with experts and non-experts about how they think Incans built their structures. She also will travel to Ecuador and along with local people, build a wall harnessing their knowledge.

It is the project she submitted in her application to Creative Capital.

“Writers, filmmakers, and artists submit cutting-edge projects that will have an impact,” she says.

“Writers, filmmakers, and artists submit cutting-edge projects that will have an impact,” she says.

Five thousand people applied, and only 50 grants were awarded.

While not certain, she believes this body of work is how she was nominated for AWAW.

“This is the first time I was nominated for AWAW,” she says. “It is an honor that an art historian, curator, writer, or artist saw my work and submitted my name.”

Though nominated, she still had to submit materials for review for the AWAW award. Again, the competition was steep as only 10 women are recognized.

AWAW offers awards only to women artists over 40 years of age who have made significant contributions in their fields to date while continuing to create new work.

“We are often forgotten in mid-career as we lack the excitement of emerging artists and the longevity of well-established artists,” she says.

AWAW was founded by artist Susan Unterberg and over 20 years has awarded more than $6 million in grants to 240 women artists.

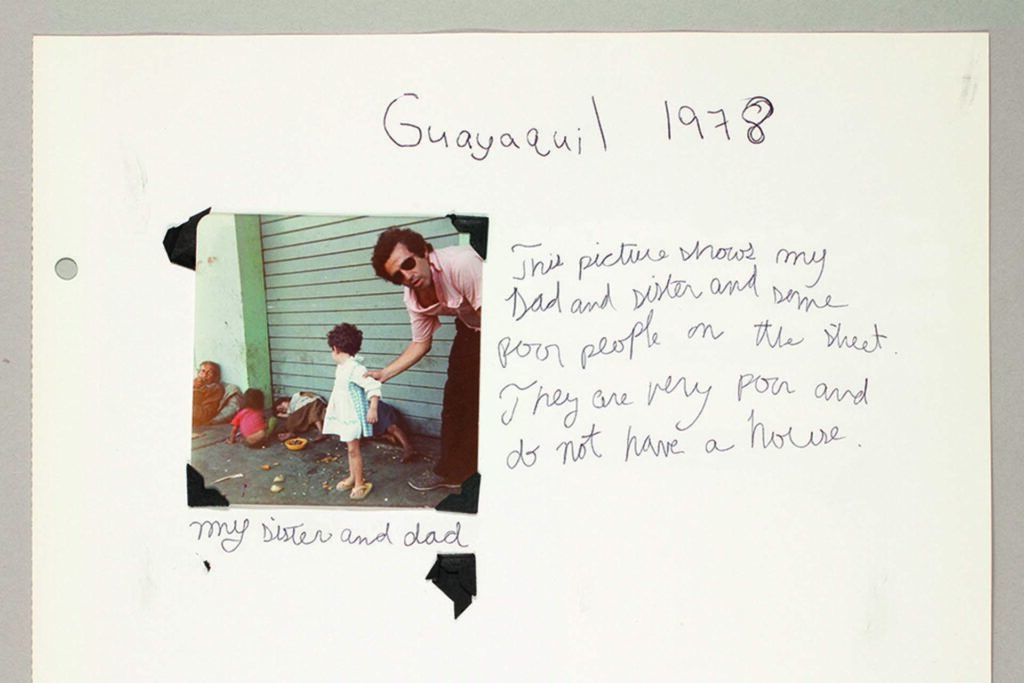

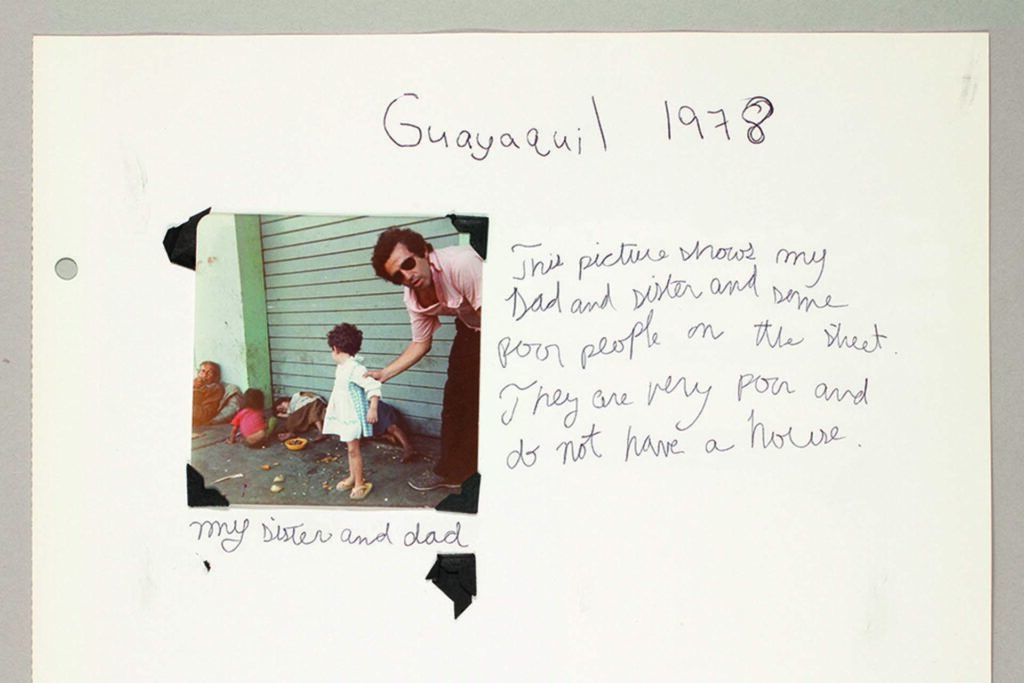

Skiversky holds an old photograph, one taken when she was a child with a 210-style camera.

“When I as a girl, we moved to Ecuador, which was an impactful experience,” she says. “I was given a camera.”

The photograph is laid out in an album of images she took as a child.

“This work and my work today are a blend of fact and fiction. They speak to an emotional truth,” she says. A truth laid in a solid foundation of stone.

“This work and my work today are a blend of fact and fiction. They speak to an emotional truth,” she says. A truth laid in a solid foundation of stone.

Skvirsky has a solo exhibition on view until Jan. 13 at El Museo Amparo in Puebla, Mexico.

“I reenacted that journey, following a path probably created by the Incas,” says Skvirsky. “While making that film, I learned about Ingapirca.”

“I reenacted that journey, following a path probably created by the Incas,” says Skvirsky. “While making that film, I learned about Ingapirca.” Those stones and the Inca Trail have become her subject matter. In addition to the film, she created several series of photographs, including one that embeds historical images with images from her journey.

Those stones and the Inca Trail have become her subject matter. In addition to the film, she created several series of photographs, including one that embeds historical images with images from her journey. “Writers, filmmakers, and artists submit cutting-edge projects that will have an impact,” she says.

“Writers, filmmakers, and artists submit cutting-edge projects that will have an impact,” she says. “This work and my work today are a blend of fact and fiction. They speak to an emotional truth,” she says. A truth laid in a solid foundation of stone.

“This work and my work today are a blend of fact and fiction. They speak to an emotional truth,” she says. A truth laid in a solid foundation of stone.

1 Comment

Inspiring!

Comments are closed.