Eric Hupe, assistant professor of art, challenges students to recreate famous works of art with household items

By Stella Katsipoutis-Varkanis

Not even quarantine could quash the creativity of students in Eric Hupe’s Introduction to Art History II course. For the assistant professor of art, teaching remotely during the last two months of the spring semester due to the coronavirus lockdown presented a unique opportunity to help his students connect with their coursework on a new level.

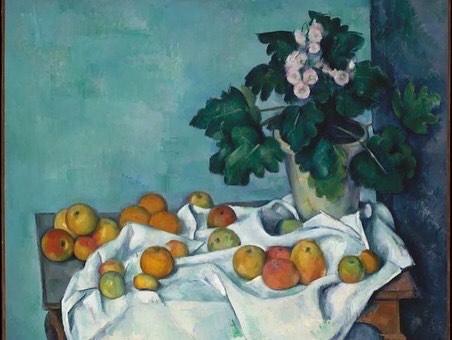

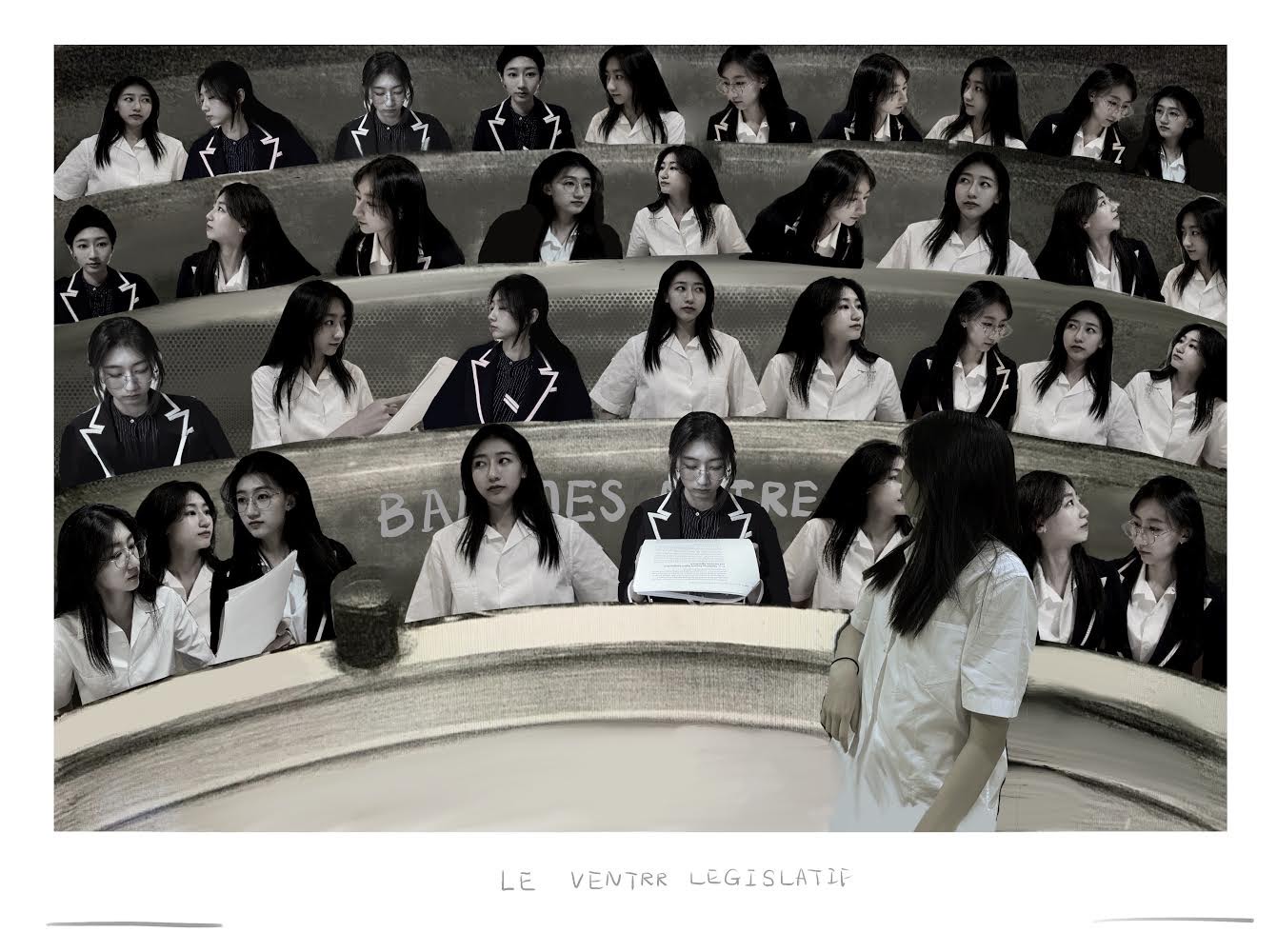

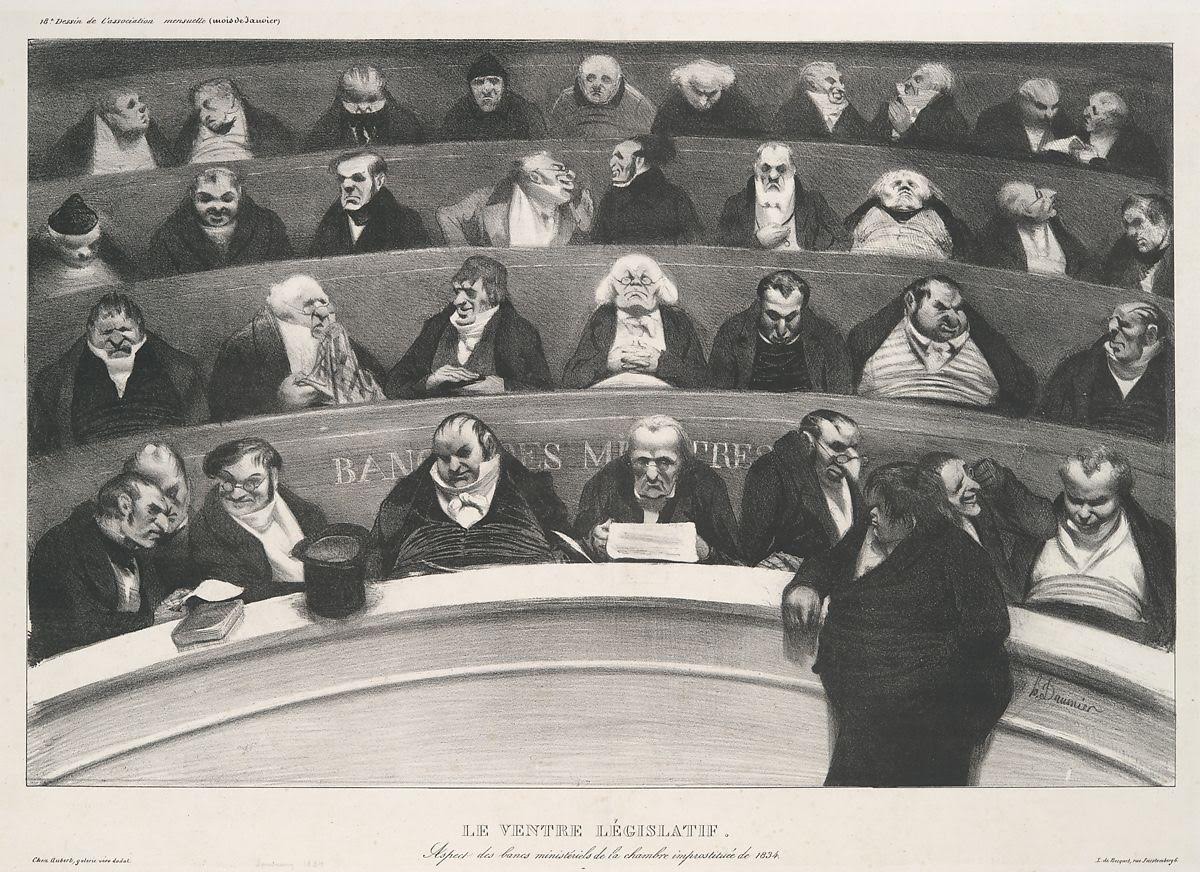

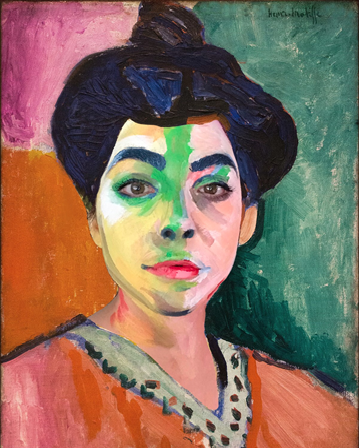

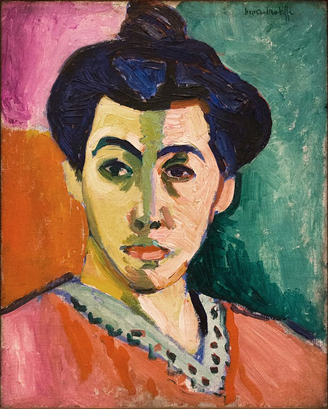

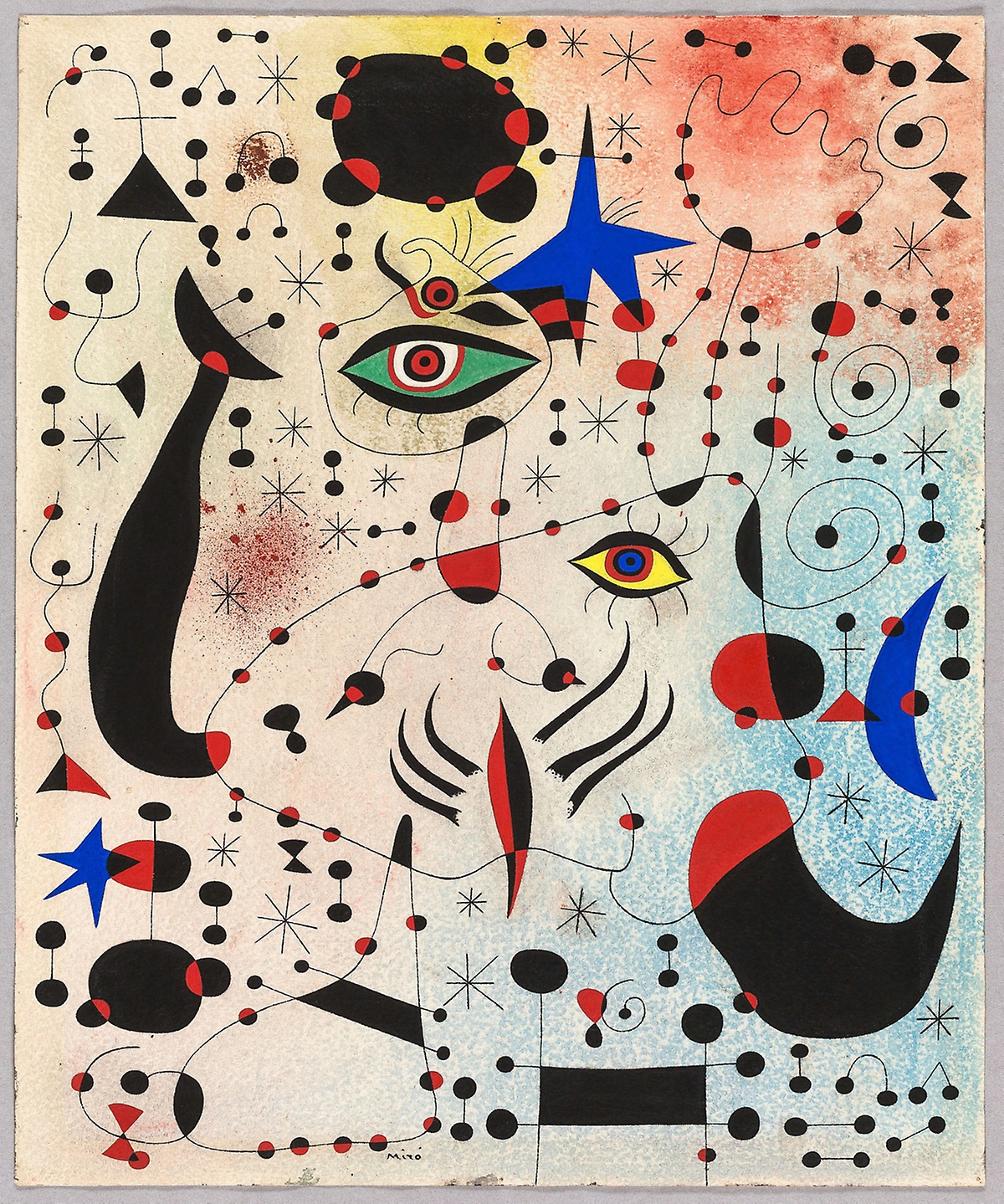

Rather than asking them to write their usual response papers on the artwork they investigated each week, Hupe challenged his ART 102 students to recreate any work of art from the specific time period they were studying in a given week—using only the items they had on hand at home.

“This moment is really asking us to distill what we think is essential for our students to learn,” Hupe says, “and I want students to immerse themselves in a work of art, be excited by the subject, and feel comfortable thinking critically about how images convey meaning.”

Hupe’s new take on his teaching method was inspired by a recent social media trend—sparked by Los Angeles’ Paul Getty Museum in March and fueled by Instagram accounts like COVID Classics and Tussen Kunst & Quarantaine—that asked art fans around the world to share photos of themselves bringing their favorite works to life.

“It’s wonderful to see people inspired by art in a time of tribulation,” he says, “and people are being inspired by things we can’t necessarily interact with in person in a museum, but instead are bringing great works of art into their homes.”

Aside from giving students something fun to do while in isolation, Hupe’s assignment brings new meaning to their study and understanding of art history. In a social media-centric era when visual images receive no more than a few seconds of their viewers’ attention, Hupe explains, the physical act of recreating a work of art requires students to intentionally slow down the process by which they analyze the piece.

“You have to think about how it’s composed and what elements work, especially when you’re making this recreation out of objects you have on hand,” he says. “So, maybe an item in the background of a painting is essential and you have to find the equivalent, or there are other features in the painting that aren’t essential to its meaning and its power, and you can leave those aside. It reveals more of the artistic invention that goes behind a work’s creation.”

Encouraging a slower, more deliberate examination of artwork was something Hupe became passionate about as a professor thanks to a study he helped conduct at the Metropolitan Museum of Art several years ago, during which he sat in a gallery and used a stopwatch to determine how much time visitors spent looking at paintings.

“On average, people spent only 30 seconds in front of works of art,” he says. “And a question I continually ask is, what can you learn from 30 seconds? A number of images, paintings, and sculptures were meant to be looked at habitually and for long periods of time for them to reveal their meaning. It’s hard for us in the 21st century—when we’re saturated with images—to demonstrate this to our students. This is a way for me to do that with them.”

Furthermore, Hupe believes the task helps build a greater sense of community among his students by giving them a unique way to share their work, and it helps them emotionally decompress during a time of global unrest.

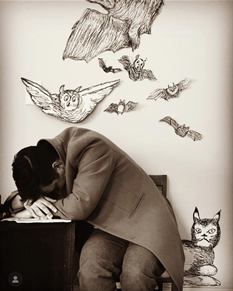

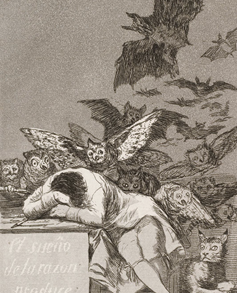

And students agree. After emailing them his own recreation of a Francisco Goya engraving as a way to announce and generate excitement about the assignment, Hupe was “floored” by the number of submissions he received from his students in the following weeks.

“I figured by kind of making a fool out of myself, maybe that would make them feel more comfortable,” Hupe says. “At first, I thought no one was going to do it, but they’ve been loving it.”

“What’s wonderful about this assignment is that it is participatory, it allows art history students to recontextualize and play with the timelessness of their art piece, and it is open to varied interpretations and processes,” says Maya Nylund ’23, who majors in art and English. “During this huge life-altering event, a lot of us are in need of some sort of outlet. And I think for people who are artistically inclined, this is a way to channel our energy creatively, with humor, and while learning.”

The challenge was so successful that Hupe is planning on incorporating it into his future art history courses, even when the coronavirus and social distancing become things of the past.

“I love the subject and I love what I do,” he says, “and I’m always trying to find ways of sharing that passion with my students. This is an opportunity to show that fun still exists in art history, and it will be exciting to see people engage with art in this way post-quarantine.”

2 Comments

Hey Eric….what a terrific thing to do…enjoyed it very much….Ed

Hi Eric,

A fantastic project!!!

Bob abd Liza

What fun!!

Comments are closed.