Notice of Online Archive

This page is no longer being updated and remains online for informational and historical purposes only. The information is accurate as of the last page update.

For questions about page contents, contact the Communications Division.

Senior art students exhibit (virtually) in Grossman Gallery

By Shannon Sigafoos

Every year, senior art students with a concentration in studio art have an exhibition in the Richard A. and Rissa W. Grossman Gallery in Williams Visual Arts Building. Despite the fact that classes were not held on campus and some students worked from a distance, this year is no different. The work of students in associate professor Karina Skvirsky’s capstone class was recently hung in the gallery in an actual exhibition and can be viewed via the gallery website.

The exhibit includes work by Jane Fergusson ’21, Hannah Ciancarelli ’21, Casey Goodwin ’21, Elle Cox ’21, Richard Ffrench ’21, Maggie DiGrande ’21, Grace Cornell ’21, and Gwen Goldman ’21.

The exhibition is a culmination of work the students did during first semester of their senior year and represents the development of their art practice. Many of these students will go on to study Honors during the spring ’21 semester.

“The importance of the students actually hanging it in real space is part of their learning, and negotiating installing and presenting art in an actual space,” said Skvirsky.

See the students’ work, featured below:

“For my capstone project, I worked in the medium of photography—specifically, digital photography. My focus for this project is on the intersection/interface between me and my imagination and the world which art creates. As a photographer, I feel that I view and picture the world through the capturing of moments and the subject explored by this project. My project began with a focus on this troubled concept: I wanted each photo to feel like a ‘moment’—one where the image could have been a second out of everyday life, yet one that has been captured in a very polished and stylized way. As I progressed with my project, I began to think about what it would look like when this ‘moment’ was dramatized, taking on more of an identity that looked like it came out of a fantasy rather than everyday life.” —Hannah Ciancarelli ’21, art and classics double major

“My work represents the idea of how I feel organized religion, specifically Christianity, has left its mark on society. My work portrays four sections, starting with a pristine and perfect typical gothic stained glass window, and slowly morphs into an unrecognizable and broken image with the remainder windows. I also wanted to emphasize the lack of religious iconography in the work. Through this work, I wanted to emphasize the notions of how at first glance, the idea of religion seems perfect and otherworldly, but when taking another closer look, you can see how corrupt and broken the religious system is.” —Grace Cornell ’21, international affairs and art major

“I live in a space of perpetual liminality, either through my skin, my place of birth, my mental state, or my environment. This liminal space acts as a threshold of transitional possibility. I am neither actualized due to the oppressive forces of society, nor not-transitioning. I live in the in-between. Through the use of photography, I aim to capture the physical and psychological experience of liminality through the lens of my race and my class. My work walks a line of questions in order to observe and explore my reaction to the space I reside in, and how my identity informs my perception. Photography is the means by which I search for resolutions, using light or the absence of light, color, and physicality to break apart the visceral, the uncomfortable, or the content within my relationship with space.” —Elle Cox ’21, psychology and art double major

“My work represents a lack of presence on Lafayette’s campus this semester due to the pandemic. I created four folk-style oil paintings on paper and incorporated small beads and other materials, such as tulle and burlap, into the paintings. The four scenes represent the four main scenes that come to mind when I imagine students hanging out at Lafayette. I painted these scenes, but removed the places people sit, the chairs on the Quad, the chairs outside Gilbert’s cafe, the chairs in the library, and the bleachers at the football field. I cut these out to show the emptiness that exists there now, but I contrasted this idea by adding shadows made of beads to these areas to show the presence or fullness that was once there. I also added beads in places where a lot of foot traffic once existed. The beads add an element of physicality as well as a handmade quality. Femininity and folk art are the two main themes present in my work through the use of folk-style painting, small personal scale, materiality, and handmade delicate details.” —Maggie DiGrande ’21, art and architecture major

“I have always been one who is fascinated by cycles of life and death and rebirth. With the onset of COVID-19, I began to observe and question how our new pandemic rules were shifting emotional landscapes. That is, how do you comfort a friend when you can’t hug them? What happens when you remove the social aspect of grief? I began this project by thinking about the changing emotional topography I was observing, but soon broadened to a longer and wider scale of time. So, I arrived at sand as a vehicle. Sand, as time. Sand, as builder and destroyer. Sand, as equalizer. Some paintings are smooth, the composition only revealed as sand strips layers of paint from canvas. Some paintings are heavy, textured, built into mountains and valleys. Here, sand creates terrain, worlds which the paint must navigate.” —Jane Fergusson ’21, math and art double major

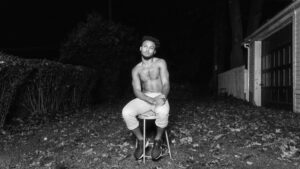

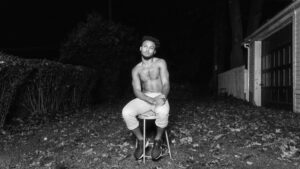

“My work focuses on the representation of the Black body in contemporary visual media—particularly on how blackness, masculinity, and vulnerability interact with each other in front of the camera. My photographs portray a gentler side of masculinity that isn’t considered ‘normal’ in mainstream media by taking a break from the traditional gender roles that stigmatize sensuality and emotion in men. In doing so, they critique toxic masculinity by discarding it. There are ways to depict Black men that don’t feed into the sexualization of the Black body and the hyper-masculine ideals and stereotypes that have proven to be harmful to Black men, women, and society as a whole. Contemporary media that focuses on these notions is unsurprisingly scarce, so I am adding to what there isn’t enough of.” —Richard Ffrench ’21, film & media studies and studio art double major

“I was born and raised in the San Fernando Valley. My father and mother both worked in Beverly Hills— my father as a tennis pro, and my mother, first as a model and then as a realtor. Now, she holds an ambiguous title and lives on a farm in rural Virginia. Los Angeles was too much for her. Cities can eat people up. My stepfather says all the time, ‘There is no geographical fix for a spiritual problem,’ and I think for the most part he is right. However, people and space are a lot more complicated than that. People adapt to the habitat that they are forced to exist in. It’s a matter of survival. Like a chameleon or a cuttlefish, we disguise ourselves and change our shape to hide in the space around us. Nobody wants to be eaten. But what color is a chameleon? Green is the cop out answer. I wanted to focus on space, and people’s ties to the space they are forced to adapt into. I use humor to deal with uncomfortable situations; it’s my defense mechanism. For this project, I explored these uncomfortable spaces in Los Angeles and tried to discuss how we disguise ourselves to fit in.” —Gwen Goldman ’21, studio art and biology major

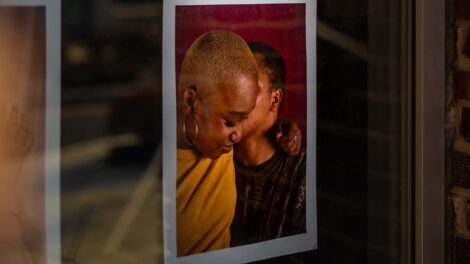

“Predominantly, I have always been a portrait photographer. I’m somewhat obsessed with people, and my work typically focuses on conscious human thought. This work, however, focuses on the subconscious, the human spirit, the often-unidentifiable feelings that weave the fabric of the soul. Portraits in this series do not contain the conventional communicative qualities of portraiture (i.e., posture, comprehensible orientation, the direct gaze), and via this ‘lack,’ they aim to demonstrate what is lost when part of the human spirit dies. And here, I don’t mean death in the literal sense; that would be another exploration entirely. At least in my own mind, the subjects of the images do not necessarily look dead, but rather, gone. In leaving us, they amplify the power of spirit and soul, the essence of humanity beyond flesh and bone. They embody discomfort, strength, distress, stillness, vulnerability … the odd concoction of all it is to be adrift, to be lost, but still living.” —Casey Goodwin ’21, mechanical engineering major