Theater department attempts to stage outdoor show to raise raunchy fist to COVID

By Stephen Wilson

If theater holds up a mirror to contemporary society, then 17th-century England was lewd and lascivious … or at least the folks who could afford a seat at the theater.

Maybe that’s why William Wycherley’s play The Country Wife fell out of production for 171 years and only made its U.S. premiere in 1931.

Still, it has remained. But anything that’s been described for centuries as “scandalous” is bound to provoke, delight, and draw a crowd.

The latter was the plan with a single outdoor performance scheduled for the last Friday in April. Directed by Michael O’Neill, associate professor of theater, students and an alumna planned and rehearsed a staged production on the steps of Pardee Hall in what gray sidewalk slabs demarcate as the Conway Plaza.

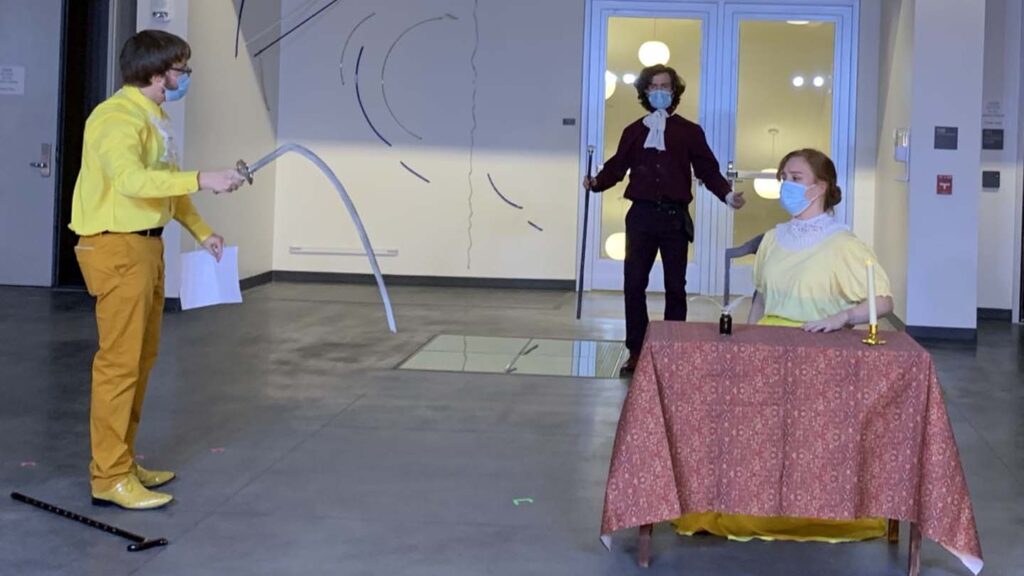

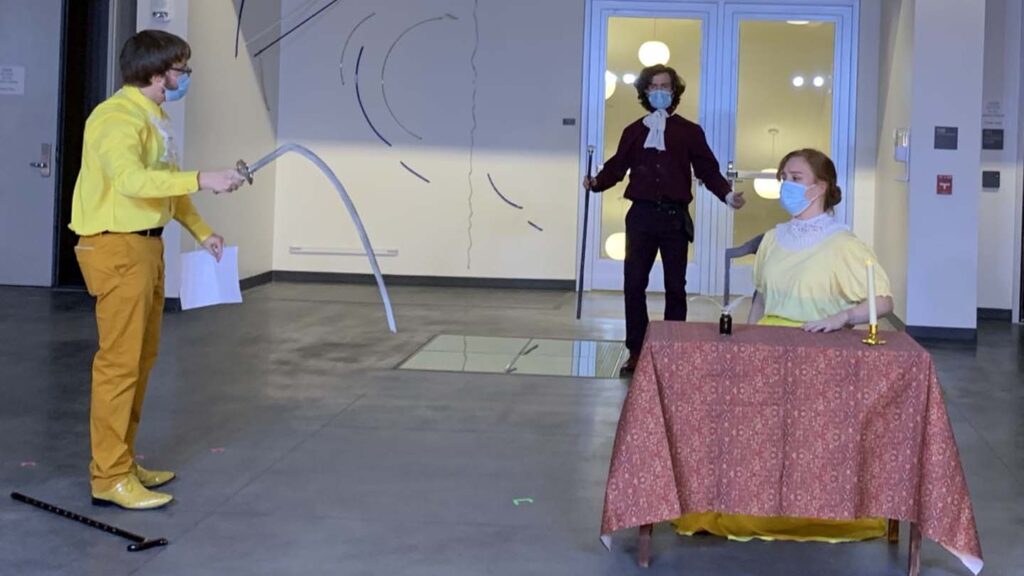

There in modern costumes, performers, festooned with swords, walking sticks, and fans, were to showcase their lingual cunning and full-on bawdy.

The story is mostly about desire and disguise. A man poses as a eunuch in order to make other men in high society see him as a non-threat, which is the perfect opportunity for him to then woo new lovers (their wives). Of course, confusion abounds as men and women fall play to the ploy while he rises to the occasion.

The show seems apt for the time as characters discuss the spread of smallpox and clap, and audience members watch as men and women behave badly. It has #MeToo written all over it. More so, the idea of authenticity—can we believe what we are being told—challenges the characters time and again.

The show seems apt for the time as characters discuss the spread of smallpox and clap, and audience members watch as men and women behave badly. It has #MeToo written all over it. More so, the idea of authenticity—can we believe what we are being told—challenges the characters time and again.

But challenges were rife off stage as well.

It’s no small list:

- 17th-century language filled with filthy puns and innuendo

- One performer put in COVID-19 quarantine and only released on the night before the show

- Wearing masks during rehearsal

- Blocking stage movement so performers remained 6 feet apart

- Adding replacement cast members just days prior to the performance

- Managing weather predictions

- Limited outdoor rehearsals with lighting and music

- And on the first night of outdoor rehearsal, a dining hall golf cart driving through the stage no less than four times en route to deliver meals to students in isolation

So why plan for the outdoors?

“Zoom fatigue” is one answer O’Neill offers, but more importantly is the need to “see live and offer live performance.”

“Witty repartee is hard in Zoom boxes and with Zoom lag,” he says. “And we can, outside, have an audience to hear and see and respond to the craft before them.”

He praises the remarkable, resilient, and hard-working cast.

Emma Kay Krebs ’20 returned to campus to help fill in when a cast member was no longer able to perform. While she only had 10 days until show time, the former theater major was happy to reclaim some of what was lost in the final months of her senior year.

Emma Kay Krebs ’20 returned to campus to help fill in when a cast member was no longer able to perform. While she only had 10 days until show time, the former theater major was happy to reclaim some of what was lost in the final months of her senior year.

O’Neill pauses a few times during the rehearsal to make stage adjustments and talk about vocal projection as the muggy night outside has their voices competing with pockets of students who are eating, reading, strolling, and scrolling on the Quad.

“There will be ambiance like this on the night of the performance,” he says. “We need to cut through that.”

The next scene, ironically, has three characters draw their swords. Two are firm and poised. The other hangs torpid like a … well, you know, dirty joke.

Then the inevitable happens.

Friday’s show night brought wind that tore down trees and snapped power lines across the valley.

The show’s outdoor venue changed to the downtown Studio Theater … until electricity was lost there too.

Ultimately, the show was taped in Buck Hall and now, in Zoom-like fashion, is available to stream.

As the swordsmen would say, foiled again.

The show seems apt for the time as characters discuss the spread of smallpox and clap, and audience members watch as men and women behave badly. It has #MeToo written all over it. More so, the idea of authenticity—can we believe what we are being told—challenges the characters time and again.

The show seems apt for the time as characters discuss the spread of smallpox and clap, and audience members watch as men and women behave badly. It has #MeToo written all over it. More so, the idea of authenticity—can we believe what we are being told—challenges the characters time and again. Emma Kay Krebs ’20

Emma Kay Krebs ’20