Evolution of the Single Family Home

By Stephen Wilson

On a corner where Fifth Avenue intersects Union Boulevard sits an inconspicuous house among the towering three-story doubles that line the street.

The house is like something unseen before in Bethlehem, Pa., and maybe any other township in America.

Architect Joe Biondo, instructor in the arts, is now self-initiating projects. He bought a small patch of land and slowly designed and built a new version of the single family home that might just upend what has been happening in America for nearly a century.

In 1947, Bill Levitt, nascent real estate developer, created what became part of the modern American dream when he bought a 7-square-mile plot of farmland and converted it into the first uniform suburban neighborhood. Those small, basement-less homes have changed over the years as today’s suburbs have grown in size and scale.

The home, beyond the basic need for shelter, has served as a symbol of status, personal freedom, and individuality for centuries. Consider how the average family size has shrunk, middle-class earnings have largely remained flat, but the average house size has grown in square footage. Despite the addition of basements and three-bay garages, today’s homes still seem to lack space as cars remain parked in driveways.

Not only are those homes big, but they are easy to build, finance, and sell. They are tailored more for investment and to highlight a person’s status rather than designed for inspired living.

“There is a great misconception of what design is,” says Biondo. “Design is not solely about how things look, but most importantly how things work. At its core, design thinking provides for multiple solutions to a singular problem and solves that problem in beautiful ways.”

Biondo, who teaches this approach in his class, knows that a few students in his course may be destined for architecture school, but the majority will go on to become engineers and politicians, academics and lawyers, economists and scientists.

Biondo, who teaches this approach in his class, knows that a few students in his course may be destined for architecture school, but the majority will go on to become engineers and politicians, academics and lawyers, economists and scientists.

“They will be members of neighborhood design review boards or campus planning committees, and may eventually have an even larger role in shaping the built environment than my colleagues will,” he says. “That’s why I provide them with the tools to be active shapers in their community and engage with confidence in the dialogue of problem-solving through design.”

Why?

Fewer than 2% of the homes built in the U.S. are designed by architects.

“I’m essentially encouraging curiosity in my students, to continually ask the question ‘why,’ the root of making quantum leaps in problem-solving,” he says.

House design has been a common topic of discussion during the pandemic as families sheltered in place and modified their residences into offices, classrooms, and every other need or service that might be met outside of the home.

Biondo doesn’t want to be critical of societal-driven trends in the housing market. Instead, he is redefining the notion of the single family home from a different lens by exploring issues of efficiency, quality vs. quantity, inspiring environments, community, inclusiveness, and aging in place.

“Welcome to what I affectionately refer to as ‘Levittown meets primitive hut,’” says Biondo. The air is redolent of mortar and slab, that faint mix of coolness, sweetness, and dust.

The structure feels modern and minimal. Materials and finishes matter—as do refining elements.

It is nothing new. The same stylistic elements have been hallmarks of Biondo’s work at the Williams Visual Arts Building, Ahart Plaza, and Easton’s new City Hall. All take time-honored and ordinary materials and push them to do extraordinary things.

Paramount is design: where the kitchen sits, the window size at the sink, where the afternoon sun will strike, where to place the rain gutters, and why there is no basement.

The house is about 1,000 square feet and has two bedrooms and 1.5 baths.

“The Moravians who settled here made buildings that had no ornament but were innovative, highly efficient, beautiful, and apportional,” says Biondo.

Standing in contrast to the light-filled and manicured interior, the exterior is tactile and curious.

The outside has brown bricks with weeping joints where mortar looks to seep from the seam, creating texture and shadow. Those joints at the northern end of the house create a gradient moving more quickly as they reach the ground.

The roof and sides are conceived as a weathertight “wrapper” covered in asphalt shingles, moving rainwater into ground gutters.

The roof and sides are conceived as a weathertight “wrapper” covered in asphalt shingles, moving rainwater into ground gutters.

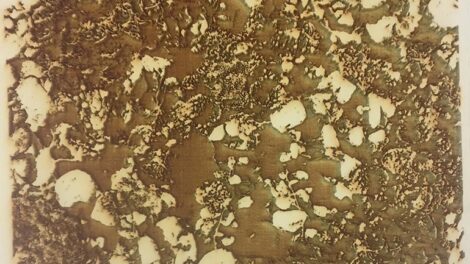

Above each window are metal shutters, patterned from the cryptobiotic soils that make up the Earth’s crust. The designs are ones Biondo collaborated on with Jim Toia, director of community-based teaching at Lafayette and chair of Karl Stirner Arts Trail.

On sunny days, the shadows cast by the shutters pattern the slab floor in several rooms in the house.

The floor plan includes a great room for living and cooking, and a spiral staircase to an overlooking loft that could serve as an art studio, family room, office, or additional bedroom.

Biondo has worked with all local contractors with locally sourced materials and products.

“In the traditional delivery of architecture, one needs to figure everything out prior to the start of construction,” he says. “But with this process, I have the time to work through the details in collaboration with subcontractors and suppliers. Time isn’t of the essence. I am assuming all the risk—it is essentially the ultimate integrated project delivery.”

And it’s a learning process. As this house is nearly finished and ready for occupancy, Biondo is actively scouting for his next plot of land where he can apply all that he has learned as he builds another project. Each new project will be influenced by site characteristics, history of place, and context; it also will aim to solve a particular societal problem through thoughtful design.

For this initial project, he believes there is a clear demand for people at both ends of the market: those eager to exit an apartment and build equity and those ready to downsize and simplify their lives. Both groups are looking beyond one-size-fits-all solutions and committed to real neighborhoods and connections to downtown settings.

“I tell my students, you will be judged by two things in this class and in life: the amount of effort you put into a task and the amount of love you put into that effort. When you do those two things at a high level, people take notice. That’s what completely elevates you and your product from the pack.”

Explore this major

Art at Lafayette

The Department of Art provides students with historical and critical understanding of art coupled with the experience of interdisciplinary artistic practice.